The major new biography of Ian Fleming by Nicholas Shakespeare contains plenty of new and exciting information about the early career of the 007 creator, and argues that the future Bond author was much more than a mere desk-bound pen-pusher during the Second World War. This builds upon new findings and research that has reassessed Ian Fleming in recent years.

The major new biography of Ian Fleming by Nicholas Shakespeare contains plenty of new and exciting information about the early career of the 007 creator, and argues that the future Bond author was much more than a mere desk-bound pen-pusher during the Second World War. This builds upon new findings and research that has reassessed Ian Fleming in recent years.

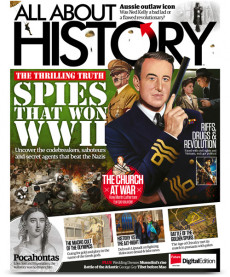

In 2012, for example, a new theory about James Bond author Ian Fleming’s role in the controversial ‘Dieppe Raid’ of 1942 was aired in a documentary screened in Canada and later shown on UK TV in 2013. The documentary, Dieppe Uncovered, which was first shown on the History Channel in Canada in August, 2012, was transmitted on the ‘Yesterday’ cable TV channel in Britain on the evening of Monday, April 1, 2013. Given all the new and intriguing information that is emerging on Fleming, the JBIFC takes the opportunity to look back on his role in the Dieppe Raid and to revisit the 2012 documentary.

The Living Highlights

The main focus of the documentary back in 2012 was on the extensive archival evidence uncovered over a 15-year period by military historian David O’Keefe concerning the secret role played by Ian Fleming in the Dieppe operation in World War Two, a role which O’Keefe believed was more substantial than previous historians had realized. Far from being merely an observer of the Raid (as some biographers had argued), it would appear that Fleming’s input into the daring, but ultimately unsuccessful, military operation may have been based on a different (and highly secret) agenda, in contrast to the official general one usually ascribed to the Dieppe Raid.

The Dieppe Raid, which took place on August 19, 1942, was an attack on the German-occupied French port of Dieppe, on the northern coast of occupied France. Over 6,000 (mainly Canadian) troops were used, supported by commandos, the Royal Navy and the RAF. The objective was to seize and temporarily hold a major French port, both to boost public morale in the UK and to reassure our Allies that Britain was serious about opening up a ‘Second Front’ and mounting an eventual invasion of Europe. The idea was also to discover what problems an invasion force might encounter and to learn valuable tactical lessons from this. However, the Raid experienced a number of major problems, including much stronger German defensive resistance than had been anticipated. Men and tanks did get ashore and into parts of the town, but over 900 Canadians were killed and 2,000 were captured. The Germans themselves were puzzled by the Raid, regarding the operation as near ‘suicidal’. Although Prime Minister Winston Churchill and Lord Mountbatten later defended the operation as providing invaluable lessons which later helped save many lives during the D-Day operation of 1944, the Dieppe Raid has had numerous critics over the years, including some former veterans, who claimed that poor planning, lack of co-ordination and weak military logistics led to unnecessary loss of life.

Fleming’s Secret Goal

Another objective of the raid was to grab vital cipher code intelligence from a French hotel in the town (a hotel which housed a Nazi operations office and a safe) and also from a German radar installation high up on the cliffs. Again, this was unsuccessful. But it is this latter aspect that led O’Keefe to develop a new theory about Ian Fleming’s role in the planning of the Raid. Far from being just a minor part of the Dieppe Raid, O’Keefe concluded that the code-book and radar objective was actually at the heart of the Raid, and that this was instigated by Ian Fleming and his boss at the Naval Intelligence Division (NID), Admiral Godfrey. In fact, according to O’Keefe, the whole raid was merely a cover diversion to allow Ian Fleming’s new special commandos, the Intelligence Assault Unit (30AU), to engage in what was known as a ‘pinch’ operation.

Created by Ian Fleming and the NID, Fleming termed 30AU his ‘official looters’, and a number of recent studies have set out the fascinating background to this highly-secret special Unit. But, on the basis of his own research, O’Keefe argued in the documentary that the main secret objective of the Dieppe Raid was to enable 30AU to steal vital code-books and spare parts for a new version of the Enigma code cipher machine which had just been introduced by the Germans a few months earlier.

Enigma and ‘Ultra’

One of the most closely-guarded secrets of World War Two was the fact that the British, using code-breaking specialists and new computer technology at a secret establishment at Bletchley Park, had been able to break the top-secret code messages being sent by the Germans, who were using what they confidently believed were ‘unbreakable’ Enigma code machines (the Enigma electro-mechanical rotor cipher machine for the encryption and decryption of secret messages had been invented by a German scientist).

This enabled the British Bletchley Park intelligence specialists to anticipate many German military tactics, which was especially crucial during the Navy’s war at sea against U-boats in the Atlantic. This top-secret intelligence operation was known as ‘Ultra’. However, in 1942, the Germans introduced a more advanced 4-rotor wheel version of Enigma, which immediately thwarted British efforts at code-breaking and suddenly halted Bletchley Park’s vital intelligence operations. For a number of frantic months, Britain was effectively ‘blind’, unable to break the new machine’s codes and read German messages.

According to the many pages of previously classified files that were uncovered by O’Keefe, in order to solve this problem, Ian Fleming and Admiral Godfrey developed the bold and ambitious plan to ‘pinch’ a 4-rotor German Enigma code machine, using 30AU commandos. Moreover, Fleming and Godfrey ensured that their new 30AU commandos secretly took part in the Dieppe Raid as part of a wider Commando Unit, although 30AU were not identified as such in official documents, such was the sensitivity of the whole NID plan. The secret 30AU platoon were led by Lt. Huntington-Whitely, who was the grandson of former Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin and was also a personal friend of Fleming. Fleming and Godfrey apparently hoped that the bigger Raid of Dieppe would fool the Germans and they would not even realize that their new Enigma code-books had been the real target and had been ‘pinched’.

Furthermore, Fleming actually attended the Dieppe Raid, waiting off-shore on board a Royal Navy ship, ready to directly receive the stolen material and immediately get it back to Bletchley Park in England. As we now know, this never happened. Indeed, perhaps one of the biggest ironies to all this is that the British were able to break the cipher codes just a few weeks later, through the dogged determination and expertise of their best Bletchley Park mathematicians and scientists. O’Keefe was not the first historian to theorize about Fleming’s role in the Dieppe Raid and to suggest that the operation was a diversion for Fleming’s secret intelligence-gathering mission. It first surfaced in the book A Man Called Intrepid (1976), a not very reliable biography of the famous Canadian spymaster (and friend of Fleming) William Stephenson, who died in 1989.

But what O’Keefe had done was to put forward valuable new details and evidence on this aspect of the Dieppe Raid, raising serious questions about the official reasons given for the Raid. As O’Keefe pointed out in the documentary, this had also enabled surviving veterans of the Dieppe Raid to understand better why the Raid was mounted, and to draw some comfort from the thought that their many fallen comrades perhaps did not die in vain after all.

Code-name 007

It is also worth noting that Ian Fleming’s 30AU went on to become a highly successful Unit in World War Two, gathering and capturing much invaluable intelligence and enemy technology. The history of the Unit has been traced in works such as Ian Fleming’s Commandos (2011), penned by Nicholas Rankin. Moreover, numerous popular magazines have tapped into all this over recent years, meeting the general public’s thirst for anything connected with Fleming, commandos, spies, codes and secret wartime intrigue. It is also interesting to note that Fleming remained fascinated by the world of secret codes and ciphers, and some of this emerged in his later James Bond books.

In the very first Bond thriller, Casino Royale (1953), for example, Fleming introduced the idea of ‘cipher’ machines quite early on in the novel. Moreover, in the fifth 007 adventure From Russia With Love (1957), to give another example, the ‘Lektor’ cipher machine was at the heart of the plot, and Fleming experts believe that this idea was based on the real-life Enigma cipher machine (a topic that was still not widely known about by the public even in the late 1950s). In a sense, Fleming also returned to the topic in his later Bond novel You Only Live Twice (1964).

As many Bond fans know, the 4-part TV biopic Fleming: The Man Who Would Be Bond, made by Ecosse Films in 2013 and directed by Mat Whitecross, which starred Dominic Cooper as the Bond author, devoted some key sequences to Fleming’s wartime role ‘in the field’. The role of his NID boss, Admiral Godfrey, was played by actor Samuel West.

The series inevitably presented Fleming as a rather Bond-like figure, and it evidently sought to exploit the glamour and action normally associated with the official James Bond movies. While highly entertaining, the series blurred fact with fiction, and can hardly be seen as a reliable or accurate exploration of Fleming’s wartime career.

The new biography of Fleming by Nicholas Shakespeare, Ian Fleming: The Complete Man, which is undoubtedly a major contribution to ‘Fleming Studies’ and all the historiography surrounding the Bond author, is much more trustworthy and explores the 007 creator’s wartime career in careful and intimate detail. Crucially, Shakespeare’s work demonstrates how Fleming’s involvement in planning and overseeing some of the most important secret espionage raids and operations of World War Two (including the Dieppe Raid) gave him numerous ideas for his later creation of the highly imaginative world of the fictional secret agent James Bond. In the process, Fleming created one of the most famous fictional spies in literary history. And for this, we shall be ever grateful.

Did You Know?

When the former Sunday Times journalist Robert Harris wrote his best-selling novel about the Enigma code-breakers, this was made into the movie Enigma in 2001, directed by Michael Apted (who had directed the 007 film The World Is Not Enough in 1999). The movie also had a haunting score by composer John Barry.

Michael Apted (1941-2021)