One of the main teaser posters for Thunderball (1965) said it all: ‘Look Out! Here Comes The Biggest Bond Of All!’ This year marks the 50th birthday of Sean Connery’s fourth movie as James Bond, a smash-hit film at the global box office which, in many ways, took ‘Bondmania’ to new and dizzying heights in the mid-1960s.

One of the main teaser posters for Thunderball (1965) said it all: ‘Look Out! Here Comes The Biggest Bond Of All!’ This year marks the 50th birthday of Sean Connery’s fourth movie as James Bond, a smash-hit film at the global box office which, in many ways, took ‘Bondmania’ to new and dizzying heights in the mid-1960s.

British television has also joined the birthday party. As the UK’s ITV-4 TV channel continues with its Autumn Bond season, with some screenings of the fourth glossy Bond espionage adventure, the JBIFC takes the opportunity to offer (00)7 points of info about the making of Thunderball, some familiar and some less so. We look back on the various production aspects of Connery’s fourth great adventure as Ian Fleming’s iconic secret agent.

What did it take to get the movie made and up on the big screen? What were the main challenges faced by EON and veteran director Terence Young, who had returned to helm his third classic James Bond production?

007 and Counting…

001: There is no doubt whatsoever that the fourth EON Bond film is a great movie, larger than life and sumptious. But the story of how Thunderball went from the printed word to the big screen is something of an epic in itself. As many dedicated Bond aficionados know, the 1965 EON film was based on Ian Fleming’s 1961 novel Thunderball, a book which the 007 author had based on a screen treatment originally developed by himself, Irish film producer Kevin McClory and screenwriter Jack Whittingham. Ian Fleming’s novel had introduced his legions of loyal readers to the criminal organisation SP.E.C.T.R.E. for the first time, a crime syndicate run by the ruthless super-villain Ernst Stavro Blofeld. It is interesting to note that the EON Bond producers, Albert ‘Cubby’ Broccoli and Harry Saltzman, had originally considered making Thunderball their first 007 movie, but a complex legal dispute (started by McClory) had broken out concerning Ian Fleming’s use for his latest novel of the Fleming-McClory-Whittingham screen material, so the two EON producers opted for Dr. No as their first 007 adventure instead. Significantly, though, the SP.E.C.T.R.E. organisation was still retained for the first EON James Bond movie, partly as an act of defiance against McClory and his Bond ownership claims.

002: Yet, just three years later, the movie world was taken by surprise: for their fourth James Bond movie Broccoli and Saltzman had come to an agreement with Kevin McClory, who had won his High Court case against Ian Fleming in November, 1963, and had been awarded certain film and TV rights to the original Thunderball material. The negotiations with EON had actually been initiated by McClory. Although he had started work on his proposed screen version of Thunderball in January, 1964 (with big star names such as Richard Burton and Laurence Harvey being mentioned by McClory as possible candidates for Bond), by September that year McClory had come to realise how difficult it would be to make a James Bond movie without Sean Connery. In the public eye, Connery was now Bond in all ways (something Sean would feel increasingly uncomfortable about). McClory had thus put out some tentative feelers to EON. At the invitation of McClory, Cubby Broccoli flew out to Ireland to see him and the final deal was apparently struck at Dublin Airport. When asked why they had eventually made the deal with McClory, Broccoli commented later: ‘We didn’t want anyone else to make Thunderball. We had the feeling that if anyone else came in and made their own Bond film, it would have been bad for our series’. McClory became producer on the movie, and Broccoli and Saltzman became executive producers. The Irish producer also agreed not to try and make his own Bond movie using his Thunderball rights for at least another 10 years.

003: Not many people realise that Guy Hamilton (1922-2016), who had directed the hugely popular Goldfinger (1964), was offered the same job on Thunderball, but had turned it down, saying he felt (at that particular stage) ‘drained of ideas’ and wanted to re-charge his creative batteries. The producers then turned back to Terence Young (1915-1994), who had helmed the first two Bond movies so successfully and efficiently. Young was a public school educated graduate of Cambridge University, and had also served as a tank commander in World War Two. In many ways, he could have been 007 himself – he was well-spoken and suave, with a liking for good clothes, fine food and other luxuries. He also had a good sense of humour, which made him popular with his crew and his actors. He had been instrumental in ‘educating’ the new young movie actor Sean Connery to be the sophisticated spy James Bond and introducing him to the high life associated with the world of Fleming’s 007, ensuring that Sean became more smartly-dressed, confident and ‘Bond-like’. Young himself had mixed feelings about returning to the James Bond series for Thunderball, but eventually agreed. He quickly realised, however, the sheer scale of the new movie and the big technical challenges it would entail, with its numerous underwater and other sequences, so he recruited three second-unit directors to help him out. Kevin McClory also proved to be very helpful at times, offering his own underwater expertise, making some useful location contacts, and helping to procure the latest hi-tech diving and other equipment available. Despite criticisms of the large number of hi-tech gadgets used in the final film, audiences were still excited about what they saw on the screen: Thunderball came across as both luxurious and ‘modern’, helped considerably by cinematographer Ted Moore’s glorious photography.

004: After the huge success of Goldfinger, the new 007 movie was given a budget of $5.6m, an enormous sum at the time and approx. six times the cost of Dr. No. Indeed, everything about Thunderball seemed ‘big’! The fourth EON film had a long 18-week shooting schedule for the principal photography, which began in February, 1965, on location in France. Shooting there started on the pre-credits sequence outside the handsome looking chapel of the Chateau D’Anet, a large and impressive mansion which had been discovered by the ever-resourceful Harry Saltzman, located approx. 40 miles to the west of Paris. The crew made a big impact locally, as everything had to be planned like a military operation. According to the late stuntman Bob Simmons (1922-1987), who doubled as the veiled widow in the pre-credit opening scenes, a large convoy of covered trucks, with Bond’s Aston Martin and a Lincoln Continental (the latter flown in specially from England), descended on the location and took over many of the local hotels. The ambitious plan to use a rocket back-pack in the pre-credits also proved a challenge. The only two pilots qualified to fly the Bell Textron jet pack had to be flown over to France for the scenes. The logistics were already proving to be quite a headache, and were just a foretaste of things to come. Indeed, as Simmons also commented, ‘the emphasis on Thunderball was size’. Nevertheless, what ended up on the screen arguably more than justified all the expense, and the sense of excitement and anticipation about the new Bond movie was very evident in all the film magazines and newspapers.

005: Director Terence Young was well-known for his unflappable ‘calm under fire’ demeanour, but even he began to feel the pressure at times of overseeing such a big and complex production. According to some reports, Young became increasingly disenchanted with the film during its final weeks of principal photography; he felt especially uneasy about all the underwater sequences, which he feared were too long, slow and repetitious. He actually left the movie as soon as all the main shooting was finished (the principal photography was completed at Pinewood in May, 1965). This created a serious and major post-production challenge in itself: so much footage had been taken for Thunderball that the rough first-cut ran to an epic 270 minutes! The ever-reliable editor Peter Hunt (in a sense) came to the rescue again; he agreed to radically restructure some parts of the movie and cut it down, including removing a key sequence where Largo shows Bond around the Disco Volante. But Hunt made it clear to studio United Artists that all this would take time and that the World Premiere of the movie, scheduled for October 21st, 1965, at the Odeon Leicester Square, would have to be delayed. The fourth Bond film eventually opened in December, 1965, first in Japan and America, and only then in the UK. Its British premiere had to take place at two cinemas in the British capital, the London Pavilion and the smaller-sized Rialto. Despite Young’s evident misgivings, though, about the final movie, he came out all guns blazing, and offered a strong defence of Thunderball, something he also did in later life. And, of course, the general public had very few clues about the enormous effort it had taken to get the movie made. Moreover, the box office business was immediately strong in all markets, with some cinemas in the USA choosing to show the movie on a near 24-hour basis. Bond was well and truly back!

006: The Bond women were especially important to the Thunderball plot. A large number of actresses were looked at for the four main female roles in Thunderball (some reports suggest up to 40 women were auditioned and screen-tested). It cost £10,000 (again, a princely sum in the 1960s) just to audition the 40 women and further narrow down the list. A considerable number of these (possibly up to 22) were considered for the key role of Dominique (‘Domino’) Derval, including Julie Christie (who was a serious contender, but seemed very nervous at her interview), Faye Dunaway, Luciana Paluzzi, Yvonne Monlaur, Marisa Menzies, Gloria Paul and Maria Buccella, to name just a few. Raquel Welch, whose photo Harry Saltzman had spotted in the October, 1964, issue of Life magazine, was actually offered the role at one point and even signed a contract, but Cubby Broccoli (apparently as a favour to Richard Zanuck at Twentieth Century Fox) reluctantly released her from the contract so that she could appear in the sci-fi movie Fantastic Voyage (1966). Faye Dunaway was also very seriously considered and negotiations took place, but in the end her agent advised her to accept an alternative film role instead (interestingly, her name re-emerged as a possible candidate for Octopussy in the early 1980s). The role of Domino in Thunderball finally went to a former Miss France of 1958, 23-year old Claudine Auger, while the Italian actress Luciana Paluzzi was given the equally important role of SP.E.C.T.R.E. assassin Fiona Volpe. Auger proved to be a good advocate and staunch defender of the idea of the modern ‘Bond woman’ in her dealings with the press. She told the UK’s Daily Mail, for example, that in her view ‘Bond women are women of the nuclear age’, and she was very keen to show the world that she had brains as well as beauty.

007: Bond star Sean Connery, ever the professional, also did his best to promote the new movie to the media. Speaking to the press in February, 1965, Sean Connery had seemed eager to start work. He commented: ‘Thunderball is the best story of them all, really. There are wonderful underwater sequences in the Bahamas and the premise is wildly exciting. I think it could be even better than the last one, but I can’t see the cycle going on past that. Though I am signed to do two more – OHMSS and one other. But who knows? American seems to lap them up’. Two days later Sean flew to France to start work on the new movie, but also stopped off for the Paris premiere of Goldfinger. However, while driving in his Aston Martin DB5 to help publicise the third Bond film in the French capital, the over-excited crowds ran after Connery and his DB5, which must have been quite unsettling for the rising star. This was just a glimpse of what lay ahead, however: relentless press intrusions and intense public interest began to haunt Connery throughout the making of Thunderball, including outside his private house in West London and on location in the Bahamas. When this was combined with the long shooting schedule, it left the Scottish 007 star more and more restless. It was also clear that his marriage to Diane Cilento was in trouble. Connery increasingly hinted that the next James Bond film would be his last. In October, 1965, he told the producers that they should shorten the shooting schedule on the next Bond film to twelve weeks only. In order to placate the star, EON eventually agreed to release him from his multi-film contract, renegotiate the terms and sign him on a one picture basis for You Only Live Twice. They hoped that this would keep Connery on board for further Bond movies. Despite Connery’s unease about being type-cast as Bond, Thunderball was an enormous success for him. He looked great on screen throughout the film, the public clearly still loved him in the role, and – in terms of his wider film career – his range and possible choice of movie roles had increased significantly because of Bond. He was box office gold. It was a great position to be in.

Did You Know?

A key and very tense sequence in Thunderball involved Bond entering Largo’s heavily-guarded luxury residence by stealth at night. Palmyra, Emilio Largo’s large mansion in Nassau, was in real-life the summer home and estate of millionaire Nicholas Sullivan and his family, who lived in Philadelphia, USA. Originally spotted by Ken Adam from the air during an early location recce, the set designer and his Thunderball location scouts had been very impressed with the house and its surroundings, especially its two swimming pools, and thought it ideal for the HQ of SP.E.C.T.R.E.’s evil No.2. During the main location filming, the crew, helped by the Miami Seaquarium, turned the large swimming pools at the residence into a tank for Largo’s sharks, filling the water with three huge tiger sharks. A naturally reluctant Sean Connery bravely agreed to get into the water and swim briefly with the sharks, which were not drugged. Trained experts were on hand to protect Sean in case there was any trouble from the sharks, and some Plexiglass sheeting was also utilised for added safety. In the event, the sharks proved very sluggish, ignoring Connery and just swimming around, much to his relief! The rest of the sequence was completed using Connery’s swimming double.

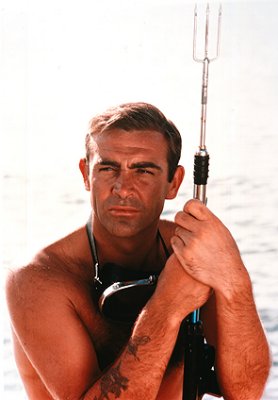

Publicity still of Adolfo Celi as Emilio Largo