It is one of the best-known James Bond novels. But where did 007 author Ian Fleming gain his inspiration for the raid on Fort Knox in his best-selling novel Goldfinger? The year 2024 will enable us to celebrate the 60th anniversary of the release of EON’s third smash-hit James Bond film and promises to see a number of fascinating articles on aspects of both the original Fleming novel and the subsequent movie, including speculation about the sheer logistics of trying to steal such a large amount of the precious metal from America’s high security gold vault (the basis of Fleming’s novel).

It is one of the best-known James Bond novels. But where did 007 author Ian Fleming gain his inspiration for the raid on Fort Knox in his best-selling novel Goldfinger? The year 2024 will enable us to celebrate the 60th anniversary of the release of EON’s third smash-hit James Bond film and promises to see a number of fascinating articles on aspects of both the original Fleming novel and the subsequent movie, including speculation about the sheer logistics of trying to steal such a large amount of the precious metal from America’s high security gold vault (the basis of Fleming’s novel).

Interestingly, the scriptwriter Richard Maibaum solved this conundrum in the EON movie version by having Auric Goldfinger (played so memorably by Gert Frobe) plant a small ‘dirty’ atomic device in the vaults of Fort Knox instead; the ‘man who loved gold’ thus hoped to render the large supply of gold stored at Fort Knox highly radioactive and effectively useless for many years, driving up the value of his own personal wealth and causing disruption to the American economy. Needless to say, James Bond thwarted this.

The Midas Touch

Back in 2009, some research by a historian raised an interesting question about where Ian Fleming possibly gained his idea from for the plot at the heart of his novel. Did the Bond creator draw his inspiration from his knowledge of a real-life plot to blow up the Bank of England in central London? This was the intriguing and controversial thesis put forward by historian Dr. Andrew Cook, and it formed the basis of a British Channel-5 TV documentary that was screened in July, 2009, narrated (very appropriately) by the late Honor ‘Pussy Galore’ Blackman. Cook also contributed a tie-in article on his research to the British espionage magazine Eyespy, entitled ‘The Real Goldfinger’. Not all historians accept Cook’s arguments, of course, but they still provide interesting food for thought for Bond aficionados. In advance of the 60th celebrations next year, the JBIFC takes the opportunity to explore this intriguing aspect of Goldfinger‘s plotline.

On His Majesty’s Secret Service

So, what was Dr. Cook’s evidence? Documents discovered by Cook, who is a specialist in intelligence history, indicated that Ian Fleming’s Fort Knox plot may have been based on the 007 author’s knowledge of a real-life plot by German intelligence agents to blow up the Bank of England back in 1914, and thereby disrupt the British economy. Fortunately, the dastardly plot, which was led by the German Kaiser’s favourite spymaster Gustav Steinhauer (1870-1930), was foiled by the Secret Service Bureau, the predecessor of both MI5 (the Security Service) and MI6 (the Secret Service).

The Bureau had been set up in 1909, consisting of a ‘domestic’ section (the forerunner to MI5) and a ‘foreign’ section (the forerunner to MI6, otherwise known as the Secret Intelligence Service). The Bureau also included a ‘Special Section’, whioch operated with just eleven men, and which was solely devoted to monitoring German spies. It was run by former Metropolitan Police ‘Special Branch’ chief Sir William Melville (who, interestingly, was known as ‘M’).

Melville (1850-1918) (pictured) had been a highly successful Special Branch Inspector during his career, helping to fight Irish nationalist terrorism and also plots by anarchists. His plain-clothes duties had also included guarding Queen Victoria, and he had later been the King’s personal bodyguard. After 32 years of police service, he had retired from the Police Special Branch in 1903. However, he had not really retired; he had been secretly recruited into a new section of the War Office, designated ‘MO3’ (later redesignated ‘MO5’). In 1909, this section had been absorbed by the new Secret Service Bureau, and became the ‘Special Section’.

Melville was a truly larger-than-life character, who was also a master of disguises. He had even used the famous escape artist Harry Houdini to help him learn the skills of picking locks, and also to train some of his own Secret Service Bureau ‘Special Section’ operatives. The ‘Special Section’ was often overstretched due to its small size but Melville, who was a ‘hands-on’ kind of boss, would regularly take on field duties himself, which he clearly enjoyed. In 1911, Melville, apparently working undercover in the field, had a real stroke of luck when he overheard a conversation on a passenger train. During the conversation, a man of German descent referred to a letter he had just received from Germany asking about Britain’s coastal defences.

This clue led Melville to arrange to have a mail intercept placed on all the correspondence of ‘F. Reimers’, a known alias of spymaster Gustav Steinhauer. The intercepted contents of the letters, in turn, led Melville to a German barber’s shop located on the Caledonian Road in London which, it emerged, was being used as a ‘letter-box’ by Steinhauer to send secret communications to his network of German spies in England. The barber shop was placed under close observation and all the mail was secretly intercepted, opened, read by Melville’s agents, carefully re-sealed, and then sent on as normal. According to a 3-page memorandum written by one of Melville’s assistants, and discovered by Andrew Cook, this was how ‘M’ came to learn about a German plot to wreck the British economy by targeting the nation’s main Bank in London.

A Pressing Engagement

The sense of urgency became acute for Melville and his ‘Special Section’ operatives. At first, they thought that the Germans might be planning to steal all the gold in the Bank of England. However, after further investigation of the heavy security measures operated by the Bank, Melville decided this was impossible. Instead, he realised the Germans were planning something more devious: the placing of high explosives in a former London Underground train tunnel which ran under the Bank. ‘M’ initiated extensive searches of the tunnel system to ruin any possibility of the German plot going ahead.

In Cook’s estimation: ‘If Britain’s Secret Service Bureau had not uncovered the plot and the Germans had succeeded, Britain would almost certainly have lost the First World War’. While this verdict is possibly exaggerated, there is no doubt that such a plan – had it succeeeded – would have dealt a big blow to British confidence in the opening year of the First World War. Britain had initially been very successful at undermining and rounding up Germany’s rather amateurish spy network in the first few months of the war, a ‘network’ which had not posed as big a threat as had been feared. Had the Bank plot succeeded, this would have certainly raised awkward questions about the competence of the Secret Service Bureau in the eyes of its political masters in Whitehall.

The Fleming Connection

Where does 007 author Ian Fleming enter into this story? As his main biographers have revealed, Fleming worked for the British Admiralty’s Naval Intelligence Department (‘NID’) during the Second World War, and it is more than likely that the highly imaginative future thriller writer, who had access to many secret ‘Eyes Only’ files intelligence during the course of his NID work, came across some information about the Bank of England plot, and this fired his curiosity.

It is well-known that Fleming used many ideas in his later post-war James Bond novels that were inspired by the extensive intelligence-related knowledge he had picked up during his wartime desk duties in Whitehall.

It is certainly quite possible that the Bank of England plot may have later influenced the Fort Knox plan in Fleming’s seventh Bond novel Goldfinger. Andrew Cook told the British press in 2009: ‘We will never know for certain, but I believe that is where Fleming got the inspiration for Goldfinger‘. Cook added: ‘Fleming no doubt found out about the real-life plot against the Bank of England in 1914 and simply transposed it to America where the equivalent target would be Fort Knox’. Ironically, the plot used in the EON film version of Goldfinger, which (as noted earlier) differed in a key way from Fleming’s ‘steal the gold’ plot concept, actually tied in more closely to the real-life 1914 plot. While Cook’s thesis could not be verified beyond doubt, the balance of probability is that he was accurate in his assessment. Ian Fleming was always on the lookout for ideas that he could re-purpose for his annual James Bond thrillers, and it seems highly probable that this is how the 007 author drew on a real-life espionage operation for his (00)7th novel. There is another fascinating aspect to all this: Fleming’s main biographers have tended to disagree about where the Bond author actually gained the idea for ‘M’ from. Was it from his knowledge about Melville, or was it from Maxwell Knight, another British spymaster? Or, much more likely, was ‘M’ based on Admiral Godfrey, Fleming’s own boss at NID?

We will probably never really know for sure. William Melville remains, however, an interesting candidate.

Did You Know?

Evidence emerged in 2010 that the famous pre-credits sequence in the movie Goldfinger (1964), where Sean Connery’s 007 arrives in a wet-suit, plants some explosives and later removes his swiming gear to reveal he is wearing a white tuxedo, may have been inspired by a real-life operation carried out by MI6 during the Second World War. Spy author Jeremy Duns put forward the theory that the iconic sequence, which was thought up by the screenwriter Paul Dehn (1912-1976), who was brought in to revise and polish aspects of Richard Maibaum’s screenplay, was based on Dehn’s knowledge of a wartime operation carried out by a British-trained Dutch spy, Peter Tazelaar, to get into Nazi-occupied Holland. Dehn, a former senior intelligence officer in the war, may have done a ‘Fleming’, and used his wartime knowledge of secret operations as the basis for certain writing concepts in his later post-war career.

Intriguingly, during the operation carried out by Peter Tazelaar on the Dutch coast, the Dutchman wore a wet-suit which he could strip off to reveal an evening suit, and thus slip into a Hotel which had become a German HQ, and which frequently saw Friday-night parties. The daring operation apparently became something of a cause celebre in British intelligence circles.

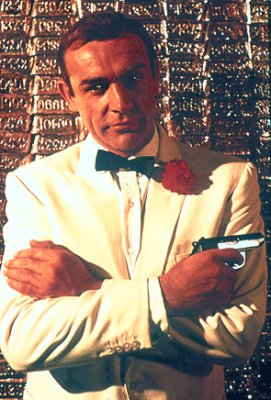

Sean Connery in a publicity pose against a backdrop of Fort Knox gold bars.