Now pay attention, 007. Many of us are very familiar with the diamond smuggling theme that was a crucial part of the storyline to Sean Connery’s sixth smash-hit James Bond movie Diamonds Are Forever (1971).

Now pay attention, 007. Many of us are very familiar with the diamond smuggling theme that was a crucial part of the storyline to Sean Connery’s sixth smash-hit James Bond movie Diamonds Are Forever (1971).

In many ways, though, the movie deviated heavily from Fleming’s original novel. On the other hand, some of the film’s early discussion of the power and appeal of diamonds (both financially and commercially), and the various real-life smuggling pipelines that had developed to facilitate the illegal trading of the precious stones across the globe, were very ‘Fleming’ and non-fiction reality was indeed touched upon when Bernard Lee’s ‘M’ testily briefs Bond and also introduces him to diamond trade expert Sir Donald Munger. Sometimes real life has an uncanny habit of being stranger than fiction, and when the James Bond author Ian Fleming took a deep interest in the various forms of diamond smuggling that took place around the world, he not only used this background material for his 007 novel Diamonds Are Forever, but also produced an investigative piece of journalism that later formed the basis of a non-fiction book on the topic. It was journalism at its best, written in Fleming’s distinctive ‘thriller’ style.

Significantly, this piece of non-fiction also stirred interest in the film world in the 1950s and early 1960s, and Fleming’s material nearly ended up as fictional thriller for the big screen. The JBIFC takes the opportunity to look back on this curious cinematic project that, sadly, never came to fruition.

Fleming and ‘Diamonds’

Ian Fleming had a big interest in precious metals, such as gold, and equally precious stones, such as diamonds, and was especially fascinated by the world of smuggling, an interest that stretched back to his love of pirate stories and the romantic idea of ‘lost treasures’ and hidden artefacts. But the world of diamonds, in particular, piqued his interest during his investigative work as a journalist. In the 1950s Fleming was even briefed on the subject at De Beers, the world-famous diamond-selling company, by Sir Percy Sillitoe, the former head of MI5 (the British domestic Security Service). Sir Percy had taken a security job with De Beers and was head of a new private intelligence agency, IDSO (International Diamond Security Organisation).

Fleming was beguiled. IDSO had been set up by De Beers to try to tackle the tremendous growth of the illegal side of the world’s diamond trade, and Fleming became fascinated by the whole operation. Fleming, of course, not only utilized the information he gathered from Sillitoe as useful authentic background information for his fourth best-selling James Bond novel Diamonds are Forever (1956), but much of the journalistic work he did on the subject (including various interviews) was also condensed into a series of newspaper articles.

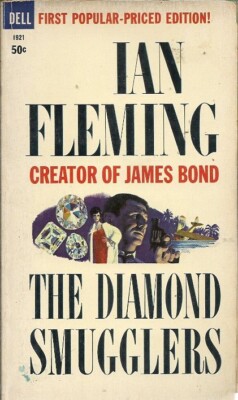

The Sunday Times engaged in some very effective publicity over Fleming’s articles, helped considerably by Fleming’s own skills at promoting his work. The Atticus column in the newspaper, for example, reported that Fleming had written about the ‘international diamond trade’ in such a way that it made ‘even his fiction plots seem almost dull in comparison’. This was, of course, a big claim, but it had the desired effect. The articles, in turn, eventually became the basis for his non-fiction book The Diamond Smugglers (1957). This, in turn, caught the interest of film-makers and the book nearly became a big-screen movie.

The Film That Nearly Was?

The word ‘nearly’ is the operative word here. In March, 2010, The Sunday Times (the late Ian Fleming’s former employer) offered some interesting new revelations on this aspect of Fleming’s career. The newspaper carried a detailed 3-page article by author and Bond expert Jeremy Duns, in which Duns sought to unravel what he called the ’50-year old mystery’ of a little-known screenplay that was specially written for a big movie version of The Diamond Smugglers.

Duns had found that, when IDSO closed down, Sir Percy Sillitoe felt that its work had not been sufficiently recognized. Sillitoe thus recruited one of IDSO’s former agents, John Collard, to ghost-write an account of the agency’s work. However, Collard’s treatment was deemed not sufficiently exciting by Denis Hamilton, the editor of The Sunday Times, so Hamilton persuaded Ian Fleming to use his professional writing and journalistic skills to spice up Collard’s story. Fleming, in turn, rewrote the whole thing and gave Collard the Bondish pseudonym ‘John Blaize’, making him the hero of the story. Blaize was a kind of quieter version of Bond, but still wore fine white silk shirts and was keen to gamble in Monte Carlo! When the story was serialized in the newspaper in September, 1957, and published in book form as The Diamond Smugglers in November that year, the film rights were quickly snapped up by the UK’s Rank Organisation.

Blaize… John Blaize

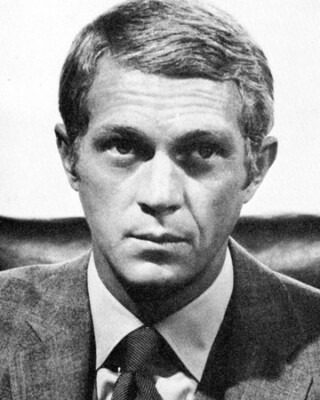

Rank, in turn, appears to have commissioned Ian Fleming to ‘prepare the film treatment’. As so often in Fleming’s career, however, the film project seems to have stalled. But what is particularly intriguing is that, at one stage, producer George Willoughby purchased the film rights from Rank and then spent some time in the early 1960s trying to re-start the project. At one point, the actor Richard Todd was down to play John Blaize. At another stage, Todd agreed to play the villain, while rising American star Steve McQueen was penciled in as John Blaize.

As Duns noted, whether or not McQueen would have been interested in, or even available for, The Diamond Smugglers is another question, ‘but it’s fascinating to think of him as a secret agent in a Fleming adaptation’. And it is another intriguing episode in the ‘what if?’ side to Fleming’s colourful dalliances with the world of film studios before he signed a full deal with EON.

American actor Steve McQueen (1930-1980)