Whoever becomes the new EON James Bond will rapidly find that their success will be very dependent on, and ultimately shaped by, the nature of the Bond 26 storyline. It has always been a huge challenge for the various screenwriters over the decades to come up with an original, interesting, memorable and – above all – thrilling 007 film screenplay, one that taps into familiar ‘Bondian’ elements but also offers something fresh and surprising.

Whoever becomes the new EON James Bond will rapidly find that their success will be very dependent on, and ultimately shaped by, the nature of the Bond 26 storyline. It has always been a huge challenge for the various screenwriters over the decades to come up with an original, interesting, memorable and – above all – thrilling 007 film screenplay, one that taps into familiar ‘Bondian’ elements but also offers something fresh and surprising.

But what makes a great James Bond film screenplay or plotline? There have been many debates about this over the years and, frankly, there’s not much consensus on what constitutes a magic 007 formula. Every Bond fan naturally has an opinion, and many of us instinctively feel certain elements make for a great Bond movie. Is it possible to discern a set of regular points that should always be there?

Back in 2012, Christopher Wood (1935-2015), who penned the screenplays for The Spy Who Loved Me (1977) and Moonraker (1979), and also the tie-in novels based on his own 007 treatments, offered his own thoughts on the ‘perfect Bond Movie’.

Given all the speculation and theories about how Bond can possibly be reinvented for a post-Craig era, the JBIFC takes the opportunity to look back on Christopher Wood’s article on ‘How to Write the Perfect Bond Movie’, which appeared in issue no. 227 of the popular British sci-fi monthly magazine SFX, as part of a ‘007 Celebration’ special issue, published when Skyfall was imminent.

While numerous Bond fans will of course have their own favourite ideas about what should go into a successful and iconic Bond screenplay, and Wood’s views were very much influenced by his experiences of the Roger Moore Bond era, there may still be some themes identified by Wood that future Bond screenwriters could draw on for a new set of 007 adventures. After all, both Spy and Moonraker were spectacularly successful at the global box office, and Spy in particular regularly appears in lists of the top 007 films chosen by Bond fans. Interestingly, Spy also remained a favourite of the late Sir Roger Moore himself. Although Wood shared the writing credits for Spy with Bond screenwriting veteran Richard Maibaum, Wood had sole responsibility for Moonraker, and remained very proud of his involvement with the Bond franchise.

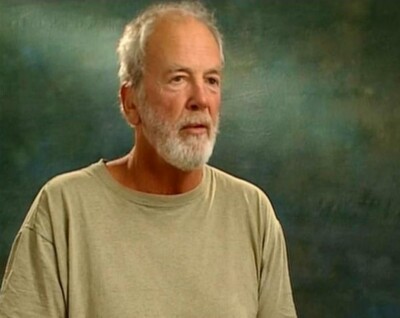

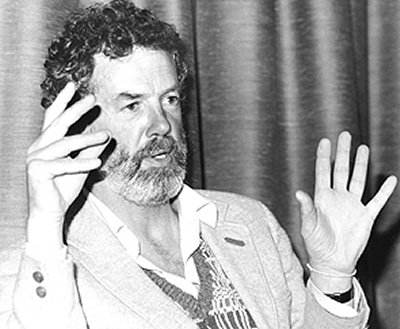

Wood, who sadly died not long after his SFX article, aged 79, was a generous and thoughtful man, who also appeared on stage at an early JBIFC convention. Born in Lambeth in London, he was a graduate of Cambridge University, and former soldier, whose main career was devoted to writing novels. In the 1970s he wrote book and screen treatments for the bawdy and hugely popular Confessions film series. He also wrote an interesting memoir, entitled James Bond, The Spy I Loved, which was published in 2006. As far as we are concerned, his SFX article on the ’12 secrets of his blockbuster craft’ are well worth revisiting.

0012 and Counting…

001: Wood asserted ‘if it ain’t broke don’t fix it’. As an avid cinema fan, he had watched hundreds of movies and felt he had ‘a pretty good idea of what buttons to push to make the audience laugh, cry or jump out of their seats’. Successful movies, he said, have a successful formula, including the Bond movies: ‘Be wary of messing with this formula’. When he was brought on board The Spy Who Loved Me, he said, the existing script was ‘decidely weird’ and bore little resemblance to the traditional Bond movie he had always enjoyed. Wood argued the screenwriter should: ‘Tick the boxes on all the things you have enjoyed in a Bond movie. Give the public what they want to see with some novel twists. Do the same thing but do it differently’.

002: Wood advised: ‘Don’t stint on the scenery. Beautiful, exotic locations are a must in a Bond movie’. On no account should a 007 screenplay ‘hold back on any majestic, awe-inspiring geographical feature with scope for derring-do’.

003: Wood asserted a Bond screenplay should: ‘Start big. It sets the tone of the movie and the audience expects it’. He recalled: ‘When I was shown the ski jump sequence in Spy I jumped in the air and punched the ceiling… That stunt alone was worth the price of admission and would get people talking’.

004: Wood believed that the screenwriter should: ‘Dream up a huge, ambitious plot, steeped in the menace of global carnage, that can be pitched in a single sentence’. Stromberg, for example, was bent on starting a new civilization under the oceans, while Drax wanted to do the same in space.

005: Wood reflected that it was advisable to: ‘Write to your star’s strengths. James Bond is Roger Moore, not Roger Moore is James Bond’. When he first took on the role, Moore was under pressure to be like Connery: ‘Bad idea’. In Spy and Moonraker Roger played himself and, in Wood’s estimation, was more relaxed and persuasive in the role.

006: Wood asserted that it was important to: ‘Create a memorable villain… as powerful, crazed and intimidating as they come… Whatever his plan for world domination there will be a grain of plausibility in it… We must wallow in his evil’.

007: Wood argued that it was essential to: ‘Make Bond sweat. It can’t all be easy. Bond is a cool resourceful type, maste rof any situation – or almost any situation. It pays if sometimes Bond suffers, if we see him in real danger. He becomes human, he becomes us‘. In Moonraker, said Wood, 007 staggers away from the centrifuge and ‘we can sense what it feels like to have your brains passed through an immersion blender’.

008: According to Wood, ‘nifty gadgets’ remained a given: ‘The audience loves ’em and who does not respond to the scene in which ‘Q’ presents his latest invention or gives Bond the chance to check out the latest works in progress in his laboratory?’ Wood said he believed audiences enjoyed these scenes and ‘they would definitely feature in the screenplay of my perfect Bond movie’.

009: Wood advised: ‘Sprinkle the piece with beautiful women’, while the main heroine should be responsible, intelligent and Bond’s equal. Bond is not entirely wthout feeling, as he can occasionally refer stoically to his newly married bride, who was cruelly slaughtered at the end of On Her Majesty’s Secret Service.

0010: Wood said a Bond screenplay should: ‘Keep things flexible. A great idea can arrive at any moment (the Spy ski jump was spotted in a newspaper advertisment). Room must be made for it’. Writing a Bond screenplay is, said Wood, ‘a team effort. Anybody on the set can come up with a good idea or improve upon an existing one. There are a lot of experienced people around with several Bond movies under their belts. It pays to listen to them…’.

0011: Wood argued that was vital for the screenwriter to: ‘Defend your work. Some directors like to have the writer around on the set for any last-minute tweaks. Many don’t’. Directors, said Wood, and sometimes the actors, may have a line or a piece of business that they have dreamed up and can’t wait to slip into the movie. Wood clearly felt it was important the screenwriter had a say in this to avoid any last-minute cringe-making lines appearing.

0012: Finally, Wood said that, given all the unmade screenplays that often sit on a screenwriter’s shelf, it remained important for a screenwriter on a Bond film to ‘enjoy’ the experience and ‘Relish your moment in the sun’, as you always know a Bond film will get made, and it will always make lots of money!

No doubt some of the above might seem a little dated, especially in light of the 007 screenplays that shaped the interpretations of Bond by the three actors who followed Moore, but a number of Wood’s points arguably remain as relevant as ever to the successful Bond formula. No doubt the debate will continue. And rightly so.

Christopher Wood interviewed on stage at an early JBIFC convention.