In his autobiography When the Snow Melts (published in 1998), the Bond producer Cubby Broccoli aptly referred to ‘the brilliant John Barry’ and said his soundtracks were ‘some of the best in cinema music’.

In his autobiography When the Snow Melts (published in 1998), the Bond producer Cubby Broccoli aptly referred to ‘the brilliant John Barry’ and said his soundtracks were ‘some of the best in cinema music’.

More recently, former Bond music composer David Arnold, when he was a guest on the ClassicFM music station in the UK in May, also paid strong homage to John Barry and his 007 music, and described how listening to the music to You Only Live Twice (1967) was a truly ground-breaking moment, which gave him a burning desire to compose for movies himself.

Later this year, the fourth James Bond movie Thunderball will celebrate its 50th anniversary and, as part of the JBIFC’s celebration of the film, we offer here a few reflections on the life of the great John Barry (1933-2011), his contribution to Bond movie no. 4, and some other brief thoughts on the composer’s life and legacy.

Operation Thunderball

After the incredible success of John Barry’s music for Goldfinger (1964), it was inevitable that the EON producers would once again turn to the highly-talented composer when it came to their fourth James Bond adventure, Thunderball.

However, Barry was under no illusions about the challenge that lay ahead. For one thing, Thunderball was going to be a longer movie, and that meant, of course, that it would need more music than the previous Bond films. More importantly, Barry had some major reservations about the actual title ‘Thunderball’, and wondered how on earth he would be able to integrate the word into a main song. As he put it in a later interview, after initially agreeing to compose the film’s music, he had at first little knowledge about the movie’s plotline: ‘All I knew was that ‘Thunderball’ was the most horrendous title for a song’.

Having read in a newspaper that the Italians were now calling James Bond ‘Mr. Kiss Kiss Bang Bang’, Barry decided that this nick-name was a more viable potential title for a song, something that could still convey everything that people associated with 007 and his world.

Barry approached Cubby Broccoli and Harry Saltzman and sounded them out about his alternative title, and they approved. Moreover, the director Terence Young, who was by then shooting the movie on location, cannily integrated the title directly into the film. The nightspot in Nassau where Bond seeks temporary refuge after a dramatic foot-chase through a street carnival is called the ‘Kiss Kiss Club’.

But then things became more complicated. In the end, two songs were actually recorded for the movie’s main title theme! The first version, a rendition of ‘Mr. Kiss Kiss Bang Bang’ that was put together by Barry, was jazz-inspired, with nicely ‘Bondian’ lyrics by Leslie Bricusse (Bricusse in particular said he ‘loved’ this version). The American singer Dionne Warwick was chosen to record the song, which she did in London in September, 1964. Barry was very pleased with the result, and both he and Bricusse were convinced it would be a ‘big hit’.

Kiss Kiss Goodnight

However, just as Barry became deeply embedded in work on the main soundtrack, the Bond producers had a change of heart, and decided that – for marketing purposes – the title ‘Thunderball’ needed to be the title of the movie’s main song after all. Barry suddenly had to go back to the drawing-board (so to speak) and start again. Moreover, Bricusse was now too busy on another project, so Barry had to find an alternative lyricist for the second version of the main title song. Fortunately, he found the highly-skilled Don Black, who had written for the singer Matt Munro.

At first very excited to be doing a Bond film, Don Black also suddenly faced the same challenge that had caused a lot of soul-searching for John Barry: how to use the word ‘Thunderball’ in a song? Black decided to approach it as a kind of Shirley Bassey song, with moody lyrics delivered by a strong voice. Even more boldly, Black persuaded his old friend Tom Jones, the hugely popular young Welsh singer, to record the song.

The now-legendary recording took place on 11th October, 1964, and (as many Bond fans now know), the recording itself went down in Bond history as a very memorable event in itself: John Barry asked Jones to hold on to the very high note at the end of the song, which he did – for a very full nine seconds! As Jones himself recalled later, when he finally opened his eyes, ‘the room was spinning’ and he nearly passed out.

The song ‘Mr. Kiss Kiss Bang Bang’ was not quite dead, though. In late September, EON had hired none other than Shirley Bassey to sing the song for the end-titles to the movie. This was recorded on 12th October, 1964, just a day after Jones had recorded his main ‘Thunderball’ song. While the new version of the ‘Kiss Kiss Bang Bang’ song was very ‘Barry-esque’, with plenty of brass, it had taken eleven takes, and Barry (very reluctantly) decided it was not quite right. When Bassey was informed that the song would not now be used, she was said to be ‘furious’, and even threatened legal action. Although a settlement was reached, it soured relations for a while between Bassey and the 007 producers, although by 1971 Bassey was back – and in great style – with Diamonds Are Forever (and, again, in 1979 for Moonraker).

John Barry completed work on the main Thunderball soundtrack with some all-time great James Bond music, a range of music that more than matched the huge ambition, action and exotic glamour of the movie itself. Interestingly, at one point, he also re-used the ‘007’ theme, a highly catchy piece of music that he had composed for From Russia With Love (1963) as a kind of alternative to the main Monty Norman ‘James Bond theme’. Tellingly, such was the pressure on Barry to complete the music for Thunderball, when the LP soundtrack album was released in 1965 it only contained tracks from the first half of the movie, as Barry was still racing to fully complete the background score!

The Name’s Barry, John Barry

John Barry, of course, continued to work on the James Bond movies and arguably had a huge impact on cinema music in general. The Yorkshire-born composer very sadly died in January, 2011, aged just 77, and there were many tributes to his Oscar-winning work from across the movie and music world. Indeed, his work today is so highly regarded that it is regularly placed alongside the compositions of some of the most famous classical composers.

Barry exemplified both the 1960s as a ‘swinging’ decade and the rise of movie soundtracks for a popular mass audience, and he gave the 007 movies a highly distinctive musical identity. There have been many words written about his legacy. In 2012, the JBIFC reported on a rediscovered tape of an interview with the late composer, which had formed the basis of a new 30-minute BBC radio programme on the Oscar-winning music maestro.

It is worth reminding ourselves about the programme, as it summed up so well Barry’s long career and creative impact. The programme, entitled John Barry: The Lost Tapes and hosted by Eddi Fiegel, went out in the UK on BBC Radio-4 on Tuesday June 26, 2012, and was repeated on Saturday June 30. The story behind the new interview material was that, in the late 1990s, Eddi had recorded a rare ‘warts and all’ radio interview with the film composer. At the time, Eddi was in the process of writing a biography about Barry. The rare tape, which had been lost for a number of years, was used by Eddie in the new programme to trace the early career of Barry, and provided an opportunity to hear the blunt-speaking music maestro speak about the various stages in his rise to fame. Indeed, as Fiegel pointed out, Barry was ‘a vivid raconteur’.

The programme opened with Barry speaking about the power of emotion that film music can provide, with a typical well-scored movie gripping the viewer for 2 hours in a dark cinema: ‘I love doing that’, said Barry.

As well as talking about his early music career with his group the ‘John Barry Seven’, and about helping the singer Adam Faith (who gave Barry an opening into the film world), Barry – who started out as a Jazz musician – reflected in detail on how he educated himself in the new exciting world of Rock and Roll, and later on in what was actually required if one was to become a successful film score composer. Experimentation was the key, and being prepared to tap into new, radical forms of music. He told Fiegel that he had always had success with things that ‘went against the grain’.

Bond is Forever

Inevitably, Barry touched upon his work on the James Bond movies. At one point, when explaining the impact of the Bond music, he said that Monty Norman’s famous James Bond theme (which was arranged by Barry) had a rhythm never before heard of at the time. Significantly, Barry also revealed that he did not sit down and concoct a particular ‘Bond style’ – he said his Bond music was a combination of influences and ‘what came out of me’. By the time it came to Goldfinger (1964), Barry said he was determined to do the whole of the music for the movie – both the song and the soundtrack, in order to fully integrate them together. As Fiegel noted, it was clear that Barry was really proud of his work on Goldfinger in particular. And, as Barry himself noted, when he saw the final movie, with Robert Brownjohn’s wonderful titles, ‘I thought it was total entertainment’. In fact, audiences applauded the titles.

It was evident that, while John Barry was often easy-going and loved to recall the stories and escapades in his colourful life, he was also very single-minded, and underneath the soft demeanour there was a man of steel. The interview with Barry at one point re-visited the now famous clash with Bond producer Harry Saltzman over the theme song for Diamonds Are Forever, a song which was about ‘making love to a diamond’. Saltzman had been heavily critical of the song, just as he had also been with the lyrics to Goldfinger.

In the presence of Don Black and Cubby Broccoli, Saltzman had confronted Barry about the DAF song. After a blazing row between Barry and Harry, in which, according to Barry, Saltzman was so angry he went ‘as red as his red socks’ and stormed out, slamming the door loudly, Cubby Broccoli broke the stunned silence by saying ‘let’s have a drink’, adding ‘they’d just proceed and do it’. And the rest, as they say, is history, as DAF went on to become another fantastic hit for both Barry and singer Shirley Bassey.

Barry is Forever

As Eddi Fiegel rightly pointed out towards the end of the programme, in a short space of time in the early 1960s, John Barry rose to become an internationally sought-after film composer, and one of the ‘most successful film composers of the 20th century’. In fact, not long after Thunderball, Barry had gained his first Oscar, awarded for Born Free (1966), and this was followed just two years later by another Oscar – for The Lion in Winter (1968). Fiegel also said that the John Barry Estate was now keen to help aspiring young film composers, a stance which itself was inspired by Barry’s own keen enthusiasm when he was alive to give advice to young people coming into the movie-music industry for the first time.

Perhaps the last word should go to his close collaborator and good friend Don Black who, after working with him on Thunderball, went on to develop a highly successful music writing partnership with Barry. Writing in the UK’s Daily Mail newspaper in 2012, the Oscar-winning lyricist revealed that, since the death of John Barry had been announced, he (Don Black) had been ‘inundated by emails and texts from his fans around the world’.

Black argued in his article that John Barry had ‘revolutionised film music’ – he had ‘a way of connecting emotionally with a story’, an understanding that resulted in the most beautiful and appropriate music. Black continued: ‘Working with John was a joy, because he didn’t present you with a rough idea, but a finished product. You knew by the time you got hold of the music he would have agonised over it, rewritten it and honed it until it was perfect’. Black added: ‘He may have gone, but the gift of his music will be with us for decades to come’.

Did You Know?

It is no exaggeration to say that David Arnold is one of John Barry’s biggest fans. Arnold’s Bond music tribute album, Shaken and Stirred: The David Arnold James Bond Project, released to wide critical acclaim in 1997, included, among a number of classic 007 songs, a version of the main theme to Thunderball sung by Martin Fry. The EON producers Barbara Broccoli and Michael G. Wilson were so impressed with the Bond tribute album that they invited Arnold to score Tomorrow Never Dies (1997). Interviewed in 2009, the composer said of his Bond tribute album and EON: ‘I think it indicated to them that there was a way of keeping what was good about the old stuff and making it contemporary’.

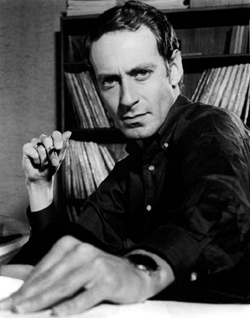

Bond composer John Barry in the 1960s