Tim Greaves reviews the 19 th James Bond movie, The World Is Not Enough

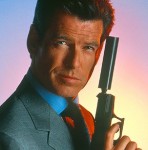

The third time is certainly the charm. Frequently during the wait for the unleashing of Pierce Brosnan’s third Bond thriller, we were drawn to the analogy that Sean Connery’s third, Goldfinger, had been his best and Roger Moore’s third, The Spy Who Loved Me had proved to be his best. As such there was obviously a great deal of expectation riding on The World Is Not Enough and thus there was no way that it could be all things to everyone. And faultless it certainly wasn’t. It is, however, Pierce Brosnan’s most superior oo7 outing to date. Unlike one or two of the convoluted contrivances of the mid-80s, the story is engaging and relatively easy to follow, near enough achieving the perfect blend of action-driven spectacle and believable human interaction. Visually too it is a triumph, from the aerial shots of Bond’s arrival in Azerbejan and the subsequent journey through the wasteland of abandoned oil fields to the snow-laden vista during Bond and Elektra’s skiing jaunt; from the magnificent overhead views of the Millennium Dome to that amazing shot of Bond swimming the length of Renard’s crippled submarine.

The opening scenes in the bank and Bond’s (amusingly interrupted) descent to street level get things off to a rousing start and pave the way for several pulse-quickening minutes of action on the River Thames. The beginning of this sequence is fine and so is the end. It’s during the middle section when the Q-Boat takes to the land that credibility is stretched beyond belief. Sure, we know the boat can function in only a few inches of water, but just what on earth was supposed to be propelling it up and down the back streets of London? We have seen this sort of excess so often it makes one shudder. The otherwise stunning freefall sequence that opens Moonraker is an obvious example, mindlessly debilitated by those few final moments featuring Jaws’ embarrassing bird impressions. And what about the tank chance in GoldenEye? Fine until someone decided it would be hilarious to have a statue charging around on the casing. But I digress. Less is more, and it’s a lesson that someone needs to wise up to once and for all. In the case of TWINE’s pre-credits it might have been far better, perhaps, to

launch the boat through the back of the canoe shed, across the street, through the restaurant and out the other side into the water. Still a credibility stretcher, for sure, but just about feasible. Nevertheless, it is what it is and the sequence as a whole stands up well enough as an exciting Bondian opener and

boasts a crackerjack conclusion when Bond plummets from the guy ropes of the balloon onto the roof of the Millennium Dome.

The race through the pipeline on a scouring pig is one of the film’s unexpected highpoints. On paper it sounds fairly mundane, but even though we know Bond isn’t going to be blown to smithereens, the tautness is sustained superbly. One could, of course, question why Bond would have needed Christmas Jones to help him disarm the bomb — good grief, he’s managed it himself on numerous enough occasions in the past — but best not to dwell on that. Better instead to savour the tension-enhancing cutaways to the control room where Elektra’s furtive behaviour is busily foreshadowing the moment when she will show her true colours.

The action inside the nuclear bunker, which could easily have been protracted to the point of tedium (I’m thinking Zorin silver mine here!), is fast-paced and breathtaking, and is all the more exciting for its brevity. The assault on the caviar factory too makes for a sizzling setpiece, running the gauntlet from the thrilling (those rotary blades whistling through the

air at Zukovsky) to the humorous (Zukovsky’s embittered “The insurance company is never going to believe this!”). It is here too that the BMW Z8 is given a chance to display its hidden talents,

particularly welcome after the disappointing catwalk

stroll afforded the Z3 in GoldenEye. Advance word that the submarine climax would be similar to the conclusion of Tomorrow Never Dies proved fortuitously unfounded (watery setting forgiven). TWINE’s climax is wholly more successful. Instead of Bond ploughing his way through platoons of henchmen like a one-man army leaving explosive

mayhem in his wake, the one-on-one scenario which constitutes his showdown with Renard brings the film to a more than satisfying conclusion. Indeed, the only action sequence in the film which doesn’t quite work is the Parahawk attack on the ski slopes. The assailants certainly look the bees knees, clad from head to toe in black, their faces hidden behind goggles and helmets. But the resulting sequence never builds into anything more than a

pedestrian destroy-by-numbers pursuit. It does boast a fine moment when Bond sees the doomed Parahawk is in fact carrying a spare ’chute and his amusement at his own wit drops from his face. But this too is immediately marred with an ill-judged

finale; where Bond should surely have been desperately looking around to find Elektra, instead he stands arrogantly fiddling with his gloves, even ignoring the chaos going on behind him. All said and done though, it’s a nice touch that later on someone (Arkov) is suitably concerned not only over the fact

that Bond is still alive but that the hardware sent to dispose of him has been wrecked.

Titles sequences are among the many anticipated facets of a Bond film, as integral to our overall enjoyment as any other. Of Daniel Kleinman’s work on the Bonds to date, GoldenEye remains his most stimulating but, accompanied by the David Arnold/Don Black/Garbage theme song, he delivers the goods here brilliantly with a shimmering multi-coloured oil-themed tableau. And wasn’t it great to see the silhouetted oo7 dropping to the ground and

limping away during the opening shots? Reminiscent of Lazenby’s sprint up the beach at the beginning of OHMSS. David Arnold’s score miraculously betters his exemplary achievements on Tomorrow Never Dies, and he conjures up a symphony of exhilarating Bondian orchestrations, from the toe-tapping action beat of ‘Ice Bandits’ to the evocative charm of ‘Christmas in Turkey’. Just one regret: The exclusion from the closing credits of Arnold’s superlative track ‘Only Myself to Blame’, presumably the decision of someone simply not bold enough to take an artistic risk. A scorchingly haunting vocal rendition of ‘Elektra’s Theme’, it is not just about Bond but

Tracy too, or more specifically his loss of Tracy and the fruitless search for love that has spanned the years since. Regardless of the delights of hearing ‘The James Bond Theme’ pounding out over the closing titles (for the first time since OHMSS, incidentally), given that Elektra is one of the few women that Bond has come even remotely close to having true feelings for, ‘Only Myself to Blame’ would have been so much more fitting.

So what of the players that held everything together? Starting at the top, Brosnan has now indisputably made the role of James Bond his own; like his predecessors (with the exception of poor old George, who was brilliant but never had the chance

to truly glitter) he now wears the part like a glove. And TWINE is awash with those little ‘Brosnanian’ touches that surfaced just once or twice in his first two entries. I’m not referring to those forced smirk-seekers (such as the straightening of his tie underwater — mildly amusing, albeit ridiculous);

I mean those moments that give you pause to think, yes, that’s exactly how James Bond should react. Take his barely suppressed ire during the briefing at Castle Thane when Tanner bypasses him during the dispersal of assignments. His expression when Elektra gives him a verbal dressing down for an apparent lack of awareness as to the identity of her aggressor is also right on the mark; he makes as if to protest, but of course everything she says is true and he knows it. Then there’s that look of tacit gratitude that crosses his face as he exchanges a final glance with Zukovsky before the big man pegs out. There are plenty of similar moments one could cite, but the apex is reached with his shock reaction when Renard utters the immortal line “There’s no point in living if you can’t feel alive”. Elektra’s duplicity won’t have come as a shock to the die-hards who followed the film’s production so intimately, but I believe that for

audiences in general this is a horrible moment of realisation and Brosnan’s reaction to the words is exceptional; I would proffer that even ‘knowing’ viewers share his moment of pain.

In the breathtakingly lovely Sophie Marceau’s performance as Elektra King we find not only a beautiful and apparently fragile creature, but a menacing, duplicitous one too. Out of the latter is born an interesting reversal of villainy. At first

our allegiance is fully with Elektra and, much like Bond after he has witnessed her post-kidnap interview tape, we care deeply for her. We despise Renard for the terrible things he is purported to have done to her. Yet by the end of the film it is the guileful Elektra that we dislike (artful to the last — “You wouldn’t kill me… you’d miss me”) and Renard who we feel just a little bit sorry for. Not only has he fallen under her spell, he will die in the belief that she loves him too, unaware that he is merely another pawn in her embittered lust for the acquisition of wealth and venomous reprisal.

As such, playing second fiddle, Renard himself may not be up there among the nastiest villains to grace a Bond story, yet he is definitely memorable.

The fact that he is impervious to pain was a shaky one to bestow upon him, with Tomorrow Never Dies’ Stamper — who bore the same ability (albeit for different reasons) — still fresh in mind. Fortunately it isn’t overplayed, so that during those moments when it is allowed to come to the fore, it is all the more effective. His uniqueness for me, however, is not in his screwed up nervous system, rather in the fact that he is a man who, as already observed, one actually ends up feeling a tad sorry for. Robert Carlyle’s superior Thespian talent makes Renard shine, particularly in those moments when his vulnerability is allowed to peer from beneath

the scarred veneer. His final farewell to Elektra is a perfect example. “This is the end,” he laments, meaning, of course, their doomed passion. This goes completely over Elektra’s head with the compassionless response “No, this is the beginning.”

Renard turns away knowing he will never see her again. Then later, in that split second when he realises he is about to die and Bond utters the line “She’s waiting for you”, knowing that Elektra is already dead there is a tangible willingness in his

reaction for death to take him too.

Denise Richards took a bit of flack when her casting as nuclear physicist Christmas Jones was announced, but she overrode all detriment admirably. Admittedly her character does little to further the plot, but that accusation could be levelled at any number of characters throughout Bond’s screen history. And in context she delivers a fine performance, headstrong and resourceful at first, yet later melting to oo7’s allure in the requisite manner, precisely as audiences would have it.

Robbie Coltrane – who had barely been given time to warm up before being rudely discarded in GoldenEye – turns in a magnificent performance as Zukovsky. Following in the wake of his acute exasperation as he sees his caviar factory being destroyed, there’s that wonderful moment as he witnesses Bond’s BMW being razored in two; his face in those few seconds says “Ahhh, at least there’s some justice.” It is the highlight of the whole caviar plant assault. In this single moment we know that, although circumstances may push him into an uneasy alliance with Bond, our hero will never have a truly reliable associate in this wily scoundrel. It’s a knowledge that adds immeasurably to the irony that he should end up saving the life of the man he supposedly despises.

Of the returning contingent, Judi Dench unsurprisingly takes the honours. Her appearances as M have already become moments to relish and her ‘confession’ scene in TWINE sees her most remarkable turn yet. Where the kidnap element – which could have floundered dismally – is adeptly handled, it is sad that it precludes Kingsley Amis’ COLONEL SUN from ever being likely to make it to the screen.

Samantha Bond is kept much in the background this time, but has successfully made Moneypenny her own. It will be a shame, if her remarks during filming are anything to go by, if she chooses not

to return to the part again.

Desmond Llewelyn’s always-anticipated arrival on screen has, by tragic default, made TWINE his finest hour. Not only is there that beautifully delivered reaction shot as Bond races through Q-Branch in pursuit of King, but also that final moment as he

descends into the floor, which has adopted a far greater poignancy than anyone could ever have imagined or intended. It was an inspired moment anyway, but the sad loss of Desmond will forever make it an eye-waterer.

I admit that I had my reservations when I heard that John Cleese was being drafted in. At the outset his inclusion just about works, particularly in the deadpan dig at Bond supposedly being on the inactive roster. But the sequence crumbles into

slapstick with the inflatable jacket demonstration and, though I admit I smiled, it’s yet another instance of the filmmakers not just stepping over the mark but taking a damned great leap into sillyland. Provided that R isn’t constantly played as the fool, where I believe his spot in future films will never match the anticipation of a Q scene, he could well become an acceptable substitute. R’s last scene in Castle Thane when he hastily shields Bond’s impropriety is indicative of a potential to fit in rather well.

Goldie’s Mr. Bullion also makes for a pleasingly unexpected addition to the pantheon of Bond villainy. Instead of a henchman in the well-trodden punch-resistant mould (as his initial appearance might indicate), he instead turns out to be a

craven fool — a “gold encrusted buffoon” as Zukovsky dubs him — and his sentence for double-cross is mercilessly and deservedly handed out by his enraged employer with appropriate swiftness.

And then there’s Maria Grazia Cuccinotta’s Cigar Girl. She does well within the confines of a decidedly slender role and her fleeting expressions of frustration at being unable to shake oo7 during their chase down the Thames are meritorious. However,

the need to keep what is already one of the longest pre-credits sequences in the series to a sensible length meant that something had to go, and so, regrettably, we lost some exposition which went some way to explaining why the Cigar Girl should

later turn up in London to try and put a bullet in Bond (something conveniently overlooked in the final cut).

Ultimately the success or failure of any film rests on the shoulders of its director, and with TWINE Michael Apted has given us what is, arguably, the finest entry in the series since The Living Daylights. The Bond movies are never less than enjoyable but are now in need of some consistency, which for better or worse they were given by the retention of directors Terence Young, Guy Hamilton and John Glen. Michael Apted, for my money, is just the man to steer oo7 successfully into the 21st century, and I shall be most disappointed if he isn’t back at the helm for Bond 20.

Before we look forward to another new Bond movie the critical and financial success of The World Is Not Enough guarantees, that regardless of what nit-picking detractors might proclaim, the James Bond film series is showing no signs whatsoever of running out of steam.