As many people know, James Bond author Ian Fleming drew some of his inspiration for 007 and his fictional espionage world from the unique knowledge he acquired during his own real-life role as an Intelligence officer in London in World War Two. But did you know that one of the men chosen to organise clandestine saboteur groups (bands of guerrillas to resist the enemy if England had been invaded in 1940) was Captain Peter Fleming, brother of Ian?

With the 76th Anniversary of the ‘Battle of Britain’ imminent, the JBIFC takes a brief look at some of the latest research on Peter Fleming’s own wartime activities, and his possible influence on the later writing career of his famous brother Ian.

Spy Another Way

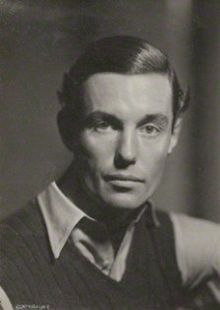

Peter Fleming (1907-1971) was a highly-regarded travel writer, novelist, and explorer; he was also the husband of film star Celia Johnson (of Brief Encounter fame), and the older brother of the future 007 author. Peter was also an expert marksman, and had joined an expedition in 1932 to explore the rivers in some of the more inhospitable parts of central Brazil. His experiences on this exciting adventure were written up and published in his best-selling book Brazilian Adventure (1933). He also went on various other trips around the world in the 1930s, and published further highly popular travel books and articles based on his experiences. When war broke out in 1939, he was a reservist in the Guards, but was soon recruited into the research wing of Military Intelligence. After active service in Norway, he was then asked in May, 1940, to come up with proposals for secret resistance networks in the UK, as part of the preparations being made for possible Nazi invasion of the British Isles.

His brother Ian Fleming, at the height of the invasion fears that gripped the country, was also serving in His Majesty’s Forces in a similar clandestine role; in Ian’s case, as an officer in the Naval Intelligence Division (NID) in Whitehall, in London, under Admiral Godfrey. A short while later, Ian came up with the idea of his own unit of ‘special’ commandos (known as ‘No. 30 Assault Unit’), who were tasked with capturing and gathering enemy hi-tech and scientific material under highly dangerous conditions. Although there is plenty of evidence available now on Ian Fleming’s 30 Assault Unit, much less is known about Peter Fleming’s own contribution to the war effort.

This is beginning to change, though, and in recent years Bond historians and other experts have found a steady trickle of tantalising new information emerging on the role of Fleming’s brother, who was an officer in what was known as the ‘London Controlling Section’ of British Military Intelligence, and was later involved in the psychological ‘dirty tricks’ side of intelligence work.

The Living Highlights

While the British RAF’s valiant ‘Few’ fought the German Luftwaffe in the skies over England in summer, 1940, detailed preparations were underway on the ground to defend the island from Nazi invasion. Britain’s land forces had been seriously weakened by the Dunkirk debacle, and a public call had gone out to raise civilian volunteer defence forces, such the Local Defence Volunteers (LDV), known later as the ‘Home Guard’. These would have supplemented the regular army in any battles to repel an invasion force.

For many years, the only main source on all this was via Peter Fleming’s own non-fiction book Invasion 1940, published in 1957 (it appeared in the USA under the title Operation Sea Lion). This book set out in a general way the main features of Hitler’s invasion plan, and the British government’s preparations to counter this. Perhaps unsurprisingly, there were very few clues to Peter Fleming’s own contribution to the latter, though.

But, in very recent years, new information has begun to emerge on the top-secret ‘stay behind’ resistance movement groups which were also secretly set up by Winston Churchill’s government, a clandestine network of volunteer units which would have carried out spying, sabotage and assassination of enemy troops had Britain been successfully occupied by the Nazis. It is only now that historians are recognising how advanced these secret plans were. Unknown to all except Churchill’s inner circle and some top army officers on a strict ‘Eyes Only’ basis, the secret plans involved young volunteers (who were sworn to secrecy) being organised in ‘Auxiliary Units’ and trained to survive in a series of secret underground hideouts scattered throughout southern England, the area which would probably have borne the brunt of fighting had Hitler put his plan, code-named ‘Operation Sea Lion’, into action. In order to maintain the high-level secrecy, the ‘stay-behind’ Units (in so far as they were even mentioned) were referred to by the deliberately bland-sounding name of ‘Observation Units’.

On His Majesty’s Service: Fleming’s Auxiliaries

Captain Peter Fleming was one of the men chosen to organise the clandestine saboteur groups in the County of Kent, in southern England (the Fleming brothers had lots of connections to Kent). Captain Fleming set up the nucleus of what was referred to as the Kent XII Corps Observation Unit. Significantly, this nucleus was later expanded to three battalions covering the whole country, and was placed under the national command of Colonel Colin Gubbins. In Kent itself there were thirty separate mini-units, and each unit or ‘patrol’ consisted of specially chosen civilians, selected for their intimate local knowledge of the area and terrain.

By day, these individuals carried on with their normal jobs, but were secretly training for their clandestine role, and were not allowed to tell even their own families about this. They were also warned that the Germans would not treat them as proper soldiers if they were caught, but would execute them as ‘spies’. Indeed, once active, the life expectancy of each volunteer would be about two weeks. But this did not deter many unit members. Captain Fleming personally chose many of the hide-outs and observation points for the secret units; he lobbied hard for the hideouts to be well-stocked with the right equipment, weapons and rations, in order that the men involved would at least get ‘a sporting chance’ of remaining ‘a thorn in the enemy’s flesh’, perhaps for some weeks. The secrecy was so great that no explicit mention was ever made of the units in official British government documents. It is only in the last few years that surviving members of the units have finally felt free to speak openly about Peter Fleming’s secret guerrilla army.

The Double-O Flemings

There were some interesting parallels between the wartime careers of Peter and Ian Fleming. As noted earlier, Peter Fleming had been recruited into Military Intelligence in early 1939, and, just five months later, Ian Fleming was recruited into the equivalent Naval version. Both men ‘networked’ in the same social and work circles, meeting some of the same people and picking up detailed knowledge of the clandestine world of spies and secret agents. In contrast to Ian, though, Peter did see some direct physical action in the field, as he was part of the small military force that operated in Norway for the brief duration of the (unsuccessful) Norway campaign in April, 1940. Peter was able to use small explosives to carry out some daring sabotage operations as the British forces retreated. The Norway campaign also saw Britain’s first real use of ‘special forces’ during the war, and all this was keenly watched by Ian, who increasingly lobbied his boss, Admiral Godfrey (reputedly the model for ‘M’), for the wider use of such types of special warfare by the Royal Navy.

While Ian’s service remained confined mainly to the Atlantic and European theatres of war, Peter’s clandestine wartime career took him to South-East Asia and India; in 1942-45 he was involved in top secret psychological warfare and military deception activities in the Far East against the Japanese, operating from a base in Britain’s huge Indian colony. Intriguingly, in the same way that Ian dreamt up various imaginative ‘deception’ operations to fool the Nazis (such as ‘Operation Goldeneye’), Peter Fleming also put his highly fertile imagination to excellent use, dreaming up various schemes to fool the Japanese Army into thinking that India was more heavily fortified than it really was (the British feared the Japanese were about to invade India). This included deliberately leaving a briefcase for the Japanese to find, which was (naturally!) full of ingeniously produced fake documents.

Bond of Brothers: The Flemings and 007

On a personal level, there was a notably close bond between the two brothers throughout their lives; Ian and Peter Fleming were devoted to each other and, after the war, Ian quickly decided that he wanted to follow in the footsteps of his brother and become a successful novelist himself. Inevitably, though, there may also have been a bit of friendly sibling rivalry on Ian’s part.

Some scholars have suggested that a spy novel by written by Peter may have given Ian an added sense of urgency to start his own spy novel series and break free from his brother’s shadow. Peter Fleming’s satirical book The Sixth Column (1952), written and published just before Ian’s first Bond novel Casino Royale appeared, had an espionage theme at its heart and was dedicated to Ian. Ian Fleming perhaps wanted to demonstrate that he, too, could write best-selling novels, but in a way that treated the world of spying in a more gritty and realistic fashion, but also with a dash of glamour.

Interestingly, Peter was not unsympathetic to Ian’s literary ambitions and may have played an instrumental role in kick-starting his brother’s writing career. Jonathan Cape seemingly had some reservations about the first James Bond book but Peter, as one of Cape’s best-selling authors, persuaded Cape to go ahead and publish it. Moreover, it has been suggested that Peter may have played a role in changing the name of M’s devoted secretary. In the first draft of Casino Royale, she was named ‘Miss Pettaval’: according to recent evidence, Peter apparently suggested that this name be changed to ‘Miss Moneypenny’. And it is also now clear that Peter was keen to help proofread his brother Ian’s Bond manuscripts, taking such close care and attention to refine the details and help Ian avoid mistakes that the Bond author began to refer to Peter as ‘Dr. Nitpick’!

When Ian Fleming very sadly passed away aged just 56 in 1964, Peter Fleming took an active role in protecting his brother’s literary legacy. Peter sat on the board of Glidrose, the company that Ian had used to hold the rights to his literary output, including the James Bond novels. In order to ensure suitable standards were maintained, Peter also played a role in the commission of the first James Bond ‘continuation’ novel, Colonel Sun (1968), penned by Kingsley Amis (writing as ‘Robert Markham’), although Ian’s widow, Ann, was not too happy about this. She viewed it as ‘commercialisation’ of her late husband’s work.

But Peter was clearly keen to defend his brother’s reputation and writings. At one point, when the religious critic Malcolm Muggeridge attacked Ian Fleming’s Bond novels, an angry Peter made a strong defence of his brother’s work, and also noted how Muggeridge had publicly vilified, within a few months of Ian’s death, ‘a friend from whom he (Muggeridge) had received nothing but kindness’. Peter’s daughters, Kate and Lucy, have also continued over the years to play an instrumental role in protecting the work and legacy of their uncle’s James Bond writings, together with his journalism and other material.

Did You Know?

In the very year that he died (1971), Peter Fleming wrote a piece that was published in the UK’s Sunday Times newspaper about the strange affair of the James Bond novel that his brother supposedly wrote six years after his death in 1964. Peter revealed to the newspaper’s readers that one day, in October, 1970, he had received ‘a short typewritten letter from an address in Hertfordshire’. A mysterious ‘Mr. A’ informed Peter that he had ‘some very unusual and I believe pleasurable news concerning your late brother which I should like to discuss with you…’.

Peter Fleming reluctantly agreed to meet the mysterious gentleman, who turned out to be a retired 73-year old bank officer who handed him a bulky typescript, on the cover of which was written the title Take Over: a James Bond thriller. ‘Mr. A’ went on to claim that his wife, who had died 3 years previously, had communicated in 1969 an extrasensory message to Mr. A.’s daughter, Vera, dictating various messages from deceased famous people from the ‘other side’, including 007 creator Ian Fleming. The Bond author had even ‘communicated’ a new James Bond story from beyond the grave! The story, a tale about a threat to dominate the world using poison gas, included such Bond characters as ‘M’ and Miss Moneypenny, but was full of words and phrases that were clearly ‘untypical of Ian’.

However, Peter Fleming had the last laugh: he sold his account of this weird episode to the Sunday Times for the then princely sum of £100. As Bond might say, a case of double-O heaven!

Author Peter Fleming in his later years