Many of the biographers of Ian Fleming have come to appreciate in recent years the full extent to which the James Bond author drew inspiration for his spy novels from various incidents and people from the real-life world of espionage, a world Fleming had worked in himself and had seen from the inside.

One possible influence on Fleming’s knowledge of the spy world was ‘Intrepid’ – the code-name of Sir William Stephenson. To help celebrate Fleming’s birthday (May 28th), the JBIFC takes a brief look back on Fleming’s close interest in Stephenson’s career.

Fifty-five years ago, in October, 1962, the Bond author, at the height of his fame for his 007 books, wrote an interesting piece in the Sunday Times newspaper on the life of ‘Intrepid’ – the secret code-name given to the Canadian master-spy Sir William Stephenson (1897-1989).

For Special Services

Who was Stephenson? He was born in Winnipeg, Canada, in January, 1897. In World War One he was a fighter pilot in the Royal Flying Corps (the precursor to what later became the Royal Air Force), and he carved out a formidable reputation for his risk-taking and bravery: he brought down 12 German planes in combat. When he himself was shot down by the Germans and captured, he managed to escape in October, 1918 (he was not to know that, just a few weeks later, the Armistice would be signed).

After the ‘Great War’, although he was labelled by some as eccentric, the single-minded and ever-resourceful Stephenson became an entrepreneur, inventor and a highly successful businessman, ending up as a millionaire in the process. But he was also increasingly interested in world affairs and, in particular, became very concerned during the 1930s about the rise of Hitler’s Nazi Germany. Stephenson was also a friend of Sir Winston Churchill, who shared Stephenson’s fears about Nazi ambitions and was very outspoken about the matter in the 1930s, making himself unpopular with those in his own party who advocated ‘appeasement’, including PM Neville Chamberlain. When Sir Winston finally became British Prime Minister in 1940, the new PM sent Stephenson to New York City to run the ‘British Security Co-ordination’ Office (BSC), which was effectively an arm of British intelligence in the USA.

As Director of BSC, as well as having the code-name ‘Intrepid’, Stephenson was also known as ‘The Quiet Canadian’ (and also as ‘Little Bill’ to both his friends and enemies). He quickly became one of Churchill’s favourite spy-masters. Along with his American team-mate General ‘Wild Bill’ Donovan (also known as ‘Big Bill’!), ‘Little Bill’ and ‘Big Bill’ became the scourge of the Nazi enemy espionage network throughout the Americas. They foiled a number of Nazi spy operations.

Licence to Kill: The role of Camp ‘X’

Interestingly, Stephenson also oversaw the running of ‘Camp X’, located at Oshawa, by Lake Ontario, near Toronto. This was a camp which carried out top-secret training of British and other Allied wartime agents, especially in the skills of sabotage and assassination, using a range of lethal Q-style gadgets. Moreover, after the USA officially entered the War in late 1941, some of the agents of the ‘Office of Strategic Services’ (OSS), which was the wartime forerunner of what subsequently became the ‘Central Intelligence Agency’ (CIA), received training at Camp X, something that Fleming was very aware of.

In his capacity as a Naval Intelligence officer, working on special ‘Ops’, Ian Fleming had been one of the visitors to the secret camp in 1943 to observe some of the training of agents in clandestine techniques (the official title of the camp in classified documents was ‘Special Training School no. 103’). Various experts on the life of Fleming and his later creation of James Bond have suggested that some of the gadgets and other secret weapons that he possibly saw being tested at Camp X may have later been one of the influences on his invention of the MI6 Quartermaster (‘Q’), and Q’s special equipment for 007 in the Bond novels.

It is also worth noting that the Stephenson/Fleming friendship continued after the War. Like Fleming, Stephenson fell in love with Jamaica, and purchased a house at Hillowtown, which overlooked Montego Bay. The two men met fairly regularly, and shared a big interest in high-speed cars. Although he had retired from the spy world to concentrate on his business interests, Stephenson retained a close interest in intelligence matters, as did Fleming.

Licence Reviewed

Significantly, Fleming, who was Foreign Manager of the Sunday Times when he wrote the Stephenson article in 1962, inserted a few reflections into the piece on his own fictional creation, secret agent James Bond, and compared the world of 007 with the real-life world of spies, as exemplified by Stephenson. Fleming wrote: ‘People often ask me how closely the hero of my thrillers, James Bond, reflects a true, live secret agent. To begin with, Bond is not in fact a hero, but an efficient and not very attractive blunt instrument in the hands of government, and though he is a meld of various qualities I noted among secret service men and commandos in the last war, he remains, of course, a highly romanticised version of the true spy. The real thing is another kind of beast altogether’.

Indeed, Stephenson, in Fleming’s estimation, was – by any standard – a real super-spy and hero. Fleming, who was himself an Intelligence co-ordinator and operations planner (in the Royal Navy’s intelligence directorate in Whitehall), had first met Stephenson in 1941, when the future Bond creator was on a plain-clothes mission to Washington with his own boss, rear-Admiral Godfrey, the director of Naval Intelligence. Fleming wrote: ‘Stephenson worked himself almost to death during the war, carrying out undercover operations and often dangerous assignments that can only be hinted at’.

Ironically, given Fleming’s assessment above, Stephenson outlived the Bond author. Fleming died in 1964, aged just 54. Stephenson died in 1989, aged 92.

Did You Know?

Coincidentally, two future British screenwriters on the EON Bond film franchise received their wartime training at Camp X: Paul Dehn, who worked for the Special Operations Executive (SOE), and Roald Dahl (who worked for BSC and was a close colleague of Fleming). Dehn, of course, worked on the screenplay for Goldfinger (1964), and Dahl developed the screen treatment for You Only Live Twice (1967).

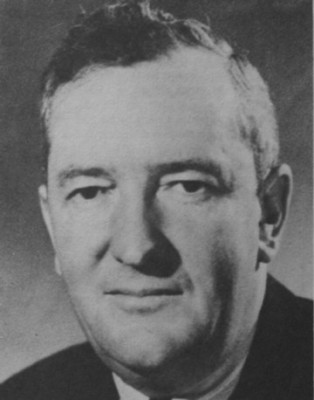

‘Intrepid’: Sir William Stephenson (1897-1989)