The espionage author and best-selling thriller writer Jeremy Duns, who is also a leading expert on the literary world of James Bond, has given a fascinating account of his re-discovery of a rare screenplay for the 1967 version of Casino Royale, the rogue non-EON movie produced by Charles K. Feldman.

The treatment was written by the famous Catch-22 author Joseph Heller, who died in 1999. Heller was invited to write a screen treatment for Feldman, the powerful Hollywood producer, but it remained for their eyes only (so to speak), and only a few elements from the Heller treatment were actually used in what eventually became the extravagant mess produced by Feldman in 1967 (which had, among others, major stars such as David Niven, Peter Sellers, Woody Allen and even former EON Bond woman Ursula Andress all playing ‘James Bond’). EON eventually acquired Feldman’s rights and made a serious version of Casino Royale with Daniel Craig as 007.

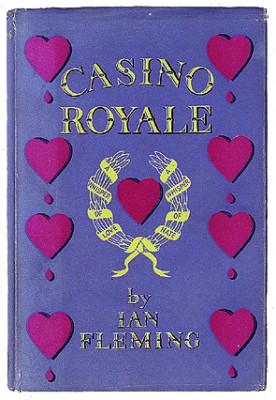

As Duns noted in his article, ‘Catch 007’ (published in the London Times newspaper on April 20th), Heller is rarely mentioned in connection with the world of James Bond. But, in early 1965, four years after the publication of Joseph Heller’s critically-acclaimed satire on military bureaucracy, Catch-22, he received a phone call from Feldman, who had obtained the film rights to Ian Fleming’s first Bond novel back in 1960. Intensely aware that James Bond had now become a huge success on the big screen via the smash-hit films produced by ‘Cubby’ Broccoli and Harry Saltzman (who had cannily purchased the screen rights for the rest of Ian Fleming’s books), Feldman had commissioned a number of screen treatments based on his precious rights to Casino Royale, including one by the legendary screenwriter Ben Hecht, which had been very faithful to Fleming’s novel.

The Feldman Project

Unfortunately, Hecht had died in April, 1964, and Feldman (a restless figure at the best of times, with quite an ego) had decided to take the project in a new direction, making it into a rival Bond film to the EON series that would be more a satire and a ‘Bond movie to end all Bond movies’. This was possibly because Feldman had sounded out the EON producers to combine forces and film Casino Royale, but negotiations had stalled. Feldman, stung by this, became determined to still plough on and milk his property for all it was worth.

Feldman offered Heller the eye-watering sum (in those days) of $150,000 to work for two weeks on a new screen treatment for Casino Royale, which would be a re-write of the Hecht script. Jeremy Duns, who has conducted some careful research into the Charles K. Feldman Collection held at the American Film Institute in Los Angeles, offered in his Times article some intriguing details on the Heller script material, which had been sitting unread for years in Feldman’s archive.

Heller agreed to work on the movie, and brought in the novelist George Mandel, a childhood friend, to help. Heller had initially believed that the job would be undemanding and fun, but had not taken into account what a paranoid and volatile character Charles K. Feldman could be. Feldman, for example, initially refused to let Heller see the Hecht script (essential, really, if Heller was to re-write it!).

Heller’s Bond

According to Duns, however, once they got going, Heller and Mandel took on the challenge of writing a Bond script with gusto, despite the difficulties of working with a Hollywood producer who did not have a concise idea of what he wanted. In all, the Feldman archive has over 100 pages of Heller and Mandel’s material. Moreover, in February, 1965, Heller sent 67 pages of script material to Feldman, representing about a third of the movie and rewritten ‘from top to bottom’, with many changes and new scenes.

Duns has read this material and was impressed. It included exciting and glamorous material, with an opening sequence clearly influenced by the EON films. But there is also material characteristically ‘Heller’, too: Heller’s script has ‘sly humour with lashings of absurdity’ in the treatment. The villains, for example, are a front group for Smersh calling themselves the ‘Society for the Collection and Harnessing of Mundane, Elemental and Cosmic Knowledge’.

Similarly, Le Chiffre is now Colonel Chiffre, who sniffs cocaine and wears a gold octopus label that squirts real octopus ink. Interestingly, James Bond himself is outfitted with an array of gadgets by MI6’s ‘Q’-like figure, Powell, who provides 007 with glasses that double as a transmitter and a cigarette lighter that could trigger an atomic explosion.

Duns provided other interesting details from Heller and Mandel’s ‘hugely entertaining’ treatment, but noted that – while it had comedic elements – it also had its own tone, with ‘a sense of menace and suspense’, and was not a spoof of the EON series but a traditional Bond film. Heller’s involvement in Feldman’s project seems to have ended in March, 1965, with Heller (pictured) now disillusioned with Feldman’s hiring of other writers who were working simultaneously on the same material. He even told Feldman to keep the money and to keep his name out of the credits.

As we now know, Feldman continued relentlessly on with the project, hiring yet more writers, and taking on at least five directors and numerous ‘big name’ actors. The budget ballooned to $12m. Feldman even tried, but failed, to persuade Sean Connery to defect from the EON series.

The resulting film, released in April, 1967, was – to use the verdict of Jeremy Duns – ‘perhaps the greatest squandering of talent in cinematic history’, the result of too many scripts and an incoherent storyline. While some of Joseph Heller’s ideas were indeed used, they were transformed beyond recognition. And, while the film did perhaps take some business away from the EON series, Connery’s fifth Bond film You Only Live Twice, released just two months later, was still a runaway success. Audiences clearly preferred a genuine Bond movie than a confused spoof.

Nevertheless, the Heller aspect is a great discovery by Duns, and helps fill in some gaps in a still relatively under-researched area of Bond’s cinematic history.