As Bond fans across the globe continue to celebrate the golden anniversary of the third smash-hit 007 movie Goldfinger (1964), which was premiered fifty years ago this month, the JBIFC takes a close look at the evolution and impact of the novel and the movie, and explores some of the familiar and less familiar aspects of the memorable villain at the heart of Sean Connery’s iconic James Bond adventure.

As Bond fans across the globe continue to celebrate the golden anniversary of the third smash-hit 007 movie Goldfinger (1964), which was premiered fifty years ago this month, the JBIFC takes a close look at the evolution and impact of the novel and the movie, and explores some of the familiar and less familiar aspects of the memorable villain at the heart of Sean Connery’s iconic James Bond adventure.

Evolution

After completing the sixth James Bond novel Dr. No (1958), Ian Fleming turned his attention to his next annual 007 adventure. The conceptual and literary evolution of what became Goldfinger (1959) is a fascinating story in itself. According to his biographers, Fleming’s wife, Anne, concerned about her husband’s declining health, had at one point persuaded the Bond author to seek help and ‘de-tox’. Fleming had thus spent ten days in April, 1956, attending a health clinic known as Enton Hall, a large Victorian mansion in Surrey, England.

Fleming had never visited such a place before, was a reluctant guest, and called it ‘Orange-juice Land’. However, ever-observant as usual, Fleming the author and journalist started to make notes about the health clinic, and some of these later helped give birth to ‘Shrublands’ in the Bond novel Thunderball (1961). But it was also at Enton that Fleming apparently absorbed much of the specialist knowledge that would go into his seventh Bond adventure Goldfinger.

The first man he encountered in the steam-bath rooms at Enton was a goldsmith named Guy Wellby, who worked in Garrick Street, London. Wellby’s family had been in the gold business for many generations, and he was able to entertain Fleming in the afternoons with many details and stories about the precious metal. And Fleming was an avid listener: in the same meticulous way that Fleming had researched the diamond industry for Diamonds Are Forever (1956), he asked Wellby numerous questions about the gold industry: the accounting side of the gold business, how gold was tested for carat, how it was transported and stored – and, especially, about how it was smuggled.

Beguiled by all the insights provided by Wellby, Fleming decided at some point to employ this information as key background context in a future 007 novel. When it came to writing Goldfinger, he also explored the nature of human obsession, equipping his new novel with a master-criminal who was in love with gold and everything connected with the precious metal.

Novelization

It is difficult to know whether Fleming’s Auric Goldfinger was inspired by any particular individual, but some scholars have suggested that one model may have been a real-life figure, the Baron Hofflinger. In the late 1920s, while he was studying the German and French languages, Fleming had been told various stories about the Baron by his friend, the writer Phyllis Bottome (1884-1963). Baron Hofflinger was, according to her, a notably short man with a strong passion, almost bordering on obsession, for horses and diamonds.

Interestingly, the name ‘Hofflinger’ sounds eerily like ‘Goldfinger’, but this may have been merely a coincidence. Just as Fleming had previously ‘borrowed’ names from his friends and enemies for various characters in his novels, a more popular theory about his choice of name for the villain of his new novel Goldfinger is that he so disliked a close neighbour in London – the Hungarian architect Erno Goldfinger (1902-1987) and his concrete ‘modernist’ designs – that the Bond author sought revenge by naming one of his nastiest baddies after the famous architect.

In fact, when Erno Goldfinger realised what Fleming had done with his name, he threatened to take legal action and halt the novel’s publication. The publishers Jonathan Cape placated and reassured the aggrieved architect that no deliberate harm was intended; this irritated Fleming in private and he threatened to change the villain’s name to ‘Goldprick’!

Goldfinger’s first name, ‘Auric’, was a typical Fleming touch: ‘AU’ is, of course, the chemical symbol for gold. And, in describing the features and character of his villain, it was clear that Fleming had created a highly memorable cross between a ruthless despot and a cold, greedy super-criminal, a man who would do anything to increase his wealth and pursue his obsession with the glittering metal. As with Fleming’s other villains, Goldfinger was also physically odd. In Fleming’s words: ‘When Goldfinger stood up, the first thing that had struck Bond was that everything was out of proportion. Goldfinger was short, not more than five feet tall’, but with a huge and ‘exactly round’ head.

Ian Fleming’s seventh James Bond novel Goldfinger was published in the UK on March 29th, 1959, with a first edition print run of 24,000 copies. The dust jacket was designed by Richard Chopping (1917-2008) and featured a skull clenching a rose between its teeth and with coins in its eye-sockets (interviewed in 2001, Chopping revealed that he thought his painting for the novel’s dustjacket was his ‘best’ one).

In many ways, the novel and its hero reflected its author’s own mood swings. By 1959, Fleming had become intensely aware of how well his 007 novels were now selling, and was increasingly looking forward to and becoming excited about all the money the book series was beginning to generate. The mood of James Bond in Goldfinger was often happy and optimistic, and for the first time in ages Bond appeared to be actually enjoying his work. There was little of the obsessive health concerns that had often preoccupied the secret agent in the previous novels.

At the same time, however, when Fleming felt tired and unenthusiastic about things, so too did Bond. Tellingly, while he was at work on Goldfinger, the Bond author called it ‘the next volume of my autobiography’. Indeed, when he had finished the book, Fleming announced to his close friend William Plomer that he had ‘run out of puff’, and would now concentrate on writing short stories about 007 instead (these eventually became For Your Eyes Only in 1960).

Interpretation

When it came to casting the main villain for the movie version of Goldfinger, the EON producers Harry Saltzman and Albert ‘Cubby’ Broccoli faced a formidable challenge. Finding a suitable actor who could do justice to the role as described by Fleming was very difficult.

At one point Orson Welles was apparently considered for the role of Goldfinger, but he demanded too much money (ironically, Welles later played Le Chiffre in the rogue version of Casino Royale in 1967, and was also wanted by Kevin McClory for the role of Blofeld in McClory’s proposed ‘independent’ 007 movie Warhead in 1978).

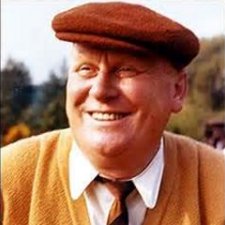

At another point, Austrian-American actor Theodore Bikel was suggested by producer Harry Saltzman, who insisted Bikel was the right choice. However, Broccoli was equally insistent that he had found the right man, the German actor Gert Frobe. Broccoli saw Frobe’s powerful performance as a child molester in a Swiss-German movie, Assault in Broad Daylight (1958). A talent scout for United Artists in Europe had spotted the German actor in the movie and had arranged that a copy be sent to Broccoli and Saltzman in London. Broccoli in particular was very impressed, and also believed it was better to go for an ‘unknown’ in the role, who could mould and make the part his own. But Saltzman and director Guy Hamilton remained unsure about Gert Frobe, especially as he could not speak fluent english and was a relative unknown outside Germany.

To appease Saltzman, Broccoli agreed to have Theodore Bikel flown over from America to the UK for an audition and a screen-test. Bikel undertook the screen-test but, while Saltzman remained enthusiastic, Broccoli thought Bikel was rather lacklustre for the role. As Broccoli put it later, ‘He was no Goldfinger’. Broccoli took the initiative and flew to Munich to see Gert Frobe’s manager, where he persuaded her to have Frobe’s sand-coloured hair dyed a deeper shade of golden red. This did the trick. When Frobe duly flew into London for a screen-test, Guy Hamilton took one look and decided Frobe was the right man after all.

Gert Frobe (1912-1988) had worked behind the scenes in theatre and cabaret and also had a big interest in opera. He initially wanted to carve out a career as a set designer but, after military service in Austria in the War, from 1945 he gradually built up a diverse range of small acting roles in films in Germany, Austria, Switzerland and France, specialising in ‘character’ parts. And he clearly had an eye-catching screen ‘presence’. As soon as Broccoli, Saltzman and Hamilton saw early rushes of Frobe as Goldfinger, they knew he had the midas touch.

His look on screen was also reinforced by some careful and thoughtful attention to certain colours in the movie: visually, the film’s Production Designer Ken Adam and Art Director Peter Murton ensured that gold was a recurring colour theme throughout the film. Everything about Auric Goldfinger was either golden or reddish-yellow, right down to his carrot-coloured hair, sun-tanned skin, and golden pistol. Even his yellow Rolls-Royce had the number plate ‘AU1’. The wardrobe department also paid close attention to the colour-coordination of Goldfinger’s clothes: the master-criminal showed a fondness for dressing in yellow, gold or brown.

And, as many Bond fans know, audiences in 1964 were treated to some now classic scenes, including James Bond’s shocking discovery of Jill Masterson (Shirley Eaton), who had died of skin suffocation when her entire body was painted gold, something that was taken directly out of Fleming’s novel (although Bond had merely heard about this in the book, not discovered her). In the movie, even the walls of Masterson’s bedroom seemed to reflect a shiny yellowish glow.

The problem of Gert Frobe’s lack of mastery of the english language was also easily resolved: Frobe was dubbed for much of the movie by Michael Collins. In fact, the only time Frobe’s real voice was briefly heard was during Goldfinger’s meeting with the gangsters at his stud farm, as Bond listened to the briefing below a model of Fort Knox. Moreover, the dialogue given to Goldfinger (and the vocal tones and emphases of Collins) led to some iconic scenes and lines in the movie, capturing the malevolent essence of the man. As Goldfinger showed his new industrial laser to Bond, he explained: ‘This is gold, Mr. Bond. All my life I have been in love with its colour, its brilliance, its divine heaviness. I welcome any enterprise that will increase my stock – which is considerable’.

It is not known what Ian Fleming thought of the casting of Frobe in the role, but the Bond author – who had visited the set of Dr. No in Jamaica and From Russia With Love in Turkey – paid a brief visit to the Pinewood Studios set of Goldfinger in March, 1964, and chatted to Sean Connery and Shirley Eaton on Pinewood’s ‘D’ Stage. Tragically, Fleming died in August, 1964, just a few weeks before the premiere of the movie in September.

But Frobe, who attended the premiere at the Odeon Leicester Square, received high praise from a wide range of film critics. One reviewer, writing in The Times (17 September, 1964), asserted that ‘Mr. Gert Frobe is astonishingly well cast in the difficult part of Goldfinger’.

Duration

The influence of Goldfinger endured for years afterwards. The movie exerted a huge impact on the James Bond series over subsequent decades and the hand of Auric Goldfinger can be detected in the franchise in a number of ways. Many of the movies arguably used the Goldfinger formula as a template – the gadgets, the cars, the music, the alluring women, the beguiling central villain, his memorable henchman, the exotic locations, and the fantastic sets.

The film not only created ‘Bond fever’ but also had a major cultural impact: as one British newspaper (The Guardian) put it in 2010 (when it included the movie in its survey of the Greatest Action Films of All Time), James Bond became: ‘Along with the Beatles, the most significant and most remunerative British cultural export of the 1960s’.

Significantly, after the ‘failure’ of On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, the producers were under huge pressure to restore the old magic and recapture the glitz of earlier Bonds such as Goldfinger. But this nearly took a bizarre twist: when story concepts were being floated for Sean Connery’s return in Diamonds Are Forever, one early idea was to have the actual return of ‘Goldfinger’ himself: the original villain in an early draft of Richard Maibaum’s screenplay was to be Auric Goldfinger’s twin brother!

Richard Maibaum (1909-1991) felt the story in Fleming’s Diamonds Are Forever lacked a strong central villain, and had always been a fan of Gert Frobe’s portrayal of Goldfinger. He decided that his concept of an evil ‘twin’ could allow the recasting of Gert Frobe. Just as Auric Goldfinger was obsessed with gold, his brother was to be obsessed with diamonds. Maibaum revealed later that he even had a line of dialogue in the draft which involved Bond meeting the villain and being told: ‘You remember my brother Auric, Mr. Bond. Mother always said he was a bit retarded’. Goldfinger’s twin was described as a power-crazed shipping magnate who housed a laser cannon in the hull of one of his fleet’s supertankers.

When Maibaum pushed for Gert Frobe to return, the producers apparently did briefly consider seeking out Frobe for the role of the ‘twin’. As Maibaum recalled in an interview in 1983, ‘We were going to approach Gert Frobe again, but it didn’t work out’. However, it is also evident that Cubby Broccoli became very uneasy about the idea, and when Tom Mankiewicz was engaged to rewrite the screenplay the main villain became Blofeld again.

But it is also interesting to note that the influence of Goldfinger remained present in other ways: Guy Hamilton, who had successfully overseen Goldfinger, returned as director for Diamonds Are Forever, Ken Adam resumed his role as Production Designer, and Shirley Bassey returned to sing the (now classic) theme song.

More recently, the Goldfinger touch has returned in the Daniel Craig Bond movies. Casino Royale gave some background on how Bond obtained his Aston Martin, while the 22nd Bond film Quantum of Solace included a direct homage to the gold-painted body death scene by having Strawberry Fields (Gemma Arterton) being found on a bed covered in crude oil. And, famously, in the 23rd 007 adventure Skyfall, the director Sam Mendes made the iconic Aston Martin DB5 a central feature of the final third of the movie, not only tapping into strong audience nostalgia but also making the car a key plot device in the story. There is no doubt that Goldfinger himself, looking down while playing his golden harp, would have strongly approved.

Did You Know?

Actor Graham Crowden (1922-2010), who had a small role as the First Sea Lord in Roger Moore’s For Your Eyes Only (1981), once played Auric Goldfinger. An edition of the BBC TV arts programme Omnibus in 1973 was devoted to ‘The British Hero’ and included discussion of the literary James Bond.

Some scenes from the Fleming novels Diamonds Are Forever and Goldfinger were recreated especially for the programme, with actor Christopher Cazenove (1943-2010) as James Bond. Remaining faithful to the novels, one scene involved Crowden’s Goldfinger standing in a medical theatre with 007 strapped to a table and being threatened by the lethal blade of a spinning saw, with Oddjob (played by Simon Walsh) standing nearby.